So the first Feminist Frequency Tropes vs. Women video has been posted, and I was very excited to see it. I was not disappointed. If you haven’t seen it yet, have a watch:

What we have here is a thorough, polished bit of media analysis with obvious effort and expense put toward editing, research, design, and production generally. If the rest of the video series is like this, it’s so worth having helped fund the Kickstarter. Even if it wasn’t like this, it would be worth it– I contributed because I saw so much value in doing the project in the first place, so the fact that it’s being done so well is icing on the cake so far as I’m concerned.

This video is the first part of a discussion on the “damsel in distress” trope, in which the female character is taken from the hero in some way– by being literally kidnapped, or possessed, or otherwise removed and her rescue made a goal for our (male) hero to accomplish. Anita Sarkeesian spends some time talking about how this trope has appeared in film before moving to video games, so that it’s clear this trope isn’t something video games invented– it existed long before they did, but video games tell stories like movies and other media tell stories, so it’s not at all unexpected that the same tropes which show up in other media would appear in video games as well. Sarkeesian gives many examples of games in which this trope is employed– the sequence of heroine after heroine calling out for help after/while being kidnapped is particularly effective– and focuses on a couple of situations in particular to talk about how how the game’s story came to be structured that way.

|

| Still from the ToM test video |

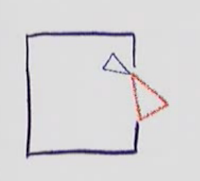

Now, if you read my blog regularly, you know that I’m all about agency. It’s more than an interest; it’s a borderline obsession. Video games are interesting to me because I enjoy playing them and have since I was a kid, but they’re also endlessly fascinating psychologically because I love to see how people who can depict agency any way they want– video game designers– end up doing so in practice. A well-known psychological test for theory of mind– the ability to recognize others as having thoughts, intentions, and emotions and comprehend what they are– is to show the subject a video involving geometric shapes on a screen moving around in a way that suggests, to a person with a normally functioning theory of mind, a story about agents. What the subject sees are a larger triangle and a smaller triangle moving in and out of a square shape, but this sequence is commonly interpreted as two figures– two agents– interacting, with one “deliberately” “blocking” the other from “leaving” the “confined space.” Autism researcher Uta Frith explains it here. That’s us applying our theory of mind to the images on the screen, making them characters.

|

| Combat. Pictured: two tanks in fierce (but slow) battle. |

If you’re old enough to have played video games on the Atari 2600, you’re quite familiar with geometric shapes being presented as having agency. Two of the favorites played in my house as a kid were Combat and Adventure, the former being a series of different games played between two people operating planes or tanks and trying to kill each other, and the latter being a single-player game in which you are a hero who attempts to take a chalice from a castle while killing dragons with a sword. Or, according to what actually appears on the screen, a square which can become attached to an arrow which changes the shape of three differently colored patterns. Even though these games weren’t realistic in the slightest, it only took a few seconds of manipulating the joystick to figure out what shape on the screen was “you.” You pushed the joystick in a particular direction, and looked for which shape on the screen was moving in that direction. That was you. Even though the shape looked nothing like you, or indeed looking like nothing in existence, you knew by its behavior that this was your representation on the screen. Your agent.

|

| Adventure. Pictured: the chalice, a dragon, a sword, and you (really). |

The thing about the damsel in distress trope is that it takes the female character away– she’s removed from the story, effectively, by being turned into a goal. We see her be captured; we see her cry out for help; we see her locked up, and maybe we see the villain torture her a bit, perhaps in view of the hero so he can have that added impetus to spring into action and save her. She’s locked in a tower, tied to the railroad tracks, in the grip of a giant ape scaling the Empire State Building, etc. She is, for all intents and purpose, incapacitated. Her job to is to look pretty and wait to be saved, while occasionally perhaps struggling and/or yelping in fear. She is a non-agent. She’s doing nothing, going nowhere.

It’s common enough to hear complaints about this trope– it’s a central feature in fairy tales, and there’s a cool children’s book called The Paper Bag Princess, now on its 25th anniversary, which subverts it completely. The notion of the woman always needing to be saved from something, and falling for her savior— what if Snow White, as it turns out, just wasn’t that into Prince Charming?– is actually more than a trope; it’s the most tired of tired cliches. But when it shows up in a video game, it’s a little different. And, I think, a lot worse, because when the damsel in distress is the focus of a video game story, it’s a story in which you, as player, are the protagonist. You control the central character of the story, the hero who must save the damsel in order to win the day, and the damsel is a thing to be won– literally. She’s a non-being, an NPC (non-player character), made of pixels and memory, and reaching her is the object of the game. Not only is she being treated as a non-agent; she is a non-agent, whereas you are not. You have goals and thoughts and feelings, as both player and character, and you are almost invariably playing a man. A straight man, presumably, because gay men don’t give a damn about kidnapped princesses.

I’m not sure if it was happenstance that just as the Damsels in Distress video came out, I started seeing people tweet and post about this parent whose three year old daughter wanted to play Pauline, the kidnapped heroine in Donkey Kong, rescuing Jump Man (aka Mario) instead of the other way around, so her father hacked the game to make it possible. You can see the result at that link; there’s a video. He says

Two days ago, she asked me if she could play as the girl and save Mario. She’s played as Princess Toadstool in Super Mario Bros. 2 and naturally just assumed she could do the same in Donkey Kong. I told her we couldn’t in that particular Mario game, she seemed really bummed out by that. So what else am I supposed to do? Now I’m up at midnight hacking the ROM, replacing Mario with Pauline.

Donkey Kong, as you know if you’ve watched the DiD video already, is one of the games discussed there in pretty significant detail. It’s awesome that this father had to skills to actually re-make the game his daughter loved in order to make the protagonist a girl saving a boy rather than the other way around, which is something most parents obviously wouldn’t have a clue how to do and probably wouldn’t trouble themselves about to begin with. I’m guessing most parents would reply “Sorry dear, but that’s not how this game works” and that would be the end of it. So this story has caught on like wildfire because of the extraordinary lengths this man went to in order to make his daughter happy, and it just happens to be the case that the thing his daughter wanted was to play herself in a video game (or at least, to play someone more like herself than Jump Man/Mario).

Or does it?

In some of the heated discussion that has already taken place about the DiD video, I’ve seen people argue that it shouldn’t matter whether the character you’re playing in a video game is at all like you and therefore there’s nothing wrong with the damsel in distress trope, which is a bit like saying that it doesn’t matter whether the “under God” part of the Pledge of Allegiance is religiously significant or not, and therefore you’d better not take it out, so help me, goddammit! Clearly it does matter, or the model in which the player’s character is male and the object of the game is to rescue a female NPC wouldn’t be so angrily defended. The player doth protest too much, and all that.

But I don’t think that most of us who do see a problem with it want to simply swap the roles around like in Donkey Kong and make all video games about female heroines saving dudes in distress– Sarkeesian sure doesn’t suggest that, and it doesn’t sound like an improvement on things to me. Of course it would be better to have more opportunities to play a female character as the protagonist, and there has been some significant improvement in that area in terms of at least making it possible for the player to have a choice about his/her character’s gender in character creation at the beginning. But really, it doesn’t seem like we suffer very much as video game players by not being able to play a character that resembles us closely– not if we’re just fine playing a square who fights dragons using an arrow. Rather, the problem with the damsel in distress trope in games is the fact that there is gender, and for half of us the gender isn’t ours, and can’t be ours. It’s clearly possible for the game to allow us to play as female, and yet it doesn’t. Instead it compels us to play a (straight) male character while dangling a female character in our faces and saying “You can’t be her. You can only save her. We assume that’s all you’d want to do, anyway.”

That’s the rub.