The discussion about AI, specifically about generative AI (whether it’s labeled as such, or just “AI”), revolves around what it means to be human, and it’s doing my head in.

Not because I have trouble grappling with the subject matter– my academic research revolved around intuitions we have about invisible agency, specifically how those intuitions guide our moral reasoning and capacity for empathy.

No, it’s doing my head in because these discussions are generally not about that, or anything like that. Instead, I’m watching a LinkedIn course recommended to me via email entitled “What is generative AI?”, and the first part of the training includes this statement (emphasis mine):

“Generative AI is not only changing almost every single profession, but it is also changing our understanding of what work is. Large parts of the production process that are repetitive or can be computational are now starting to be facilitated by AI models. All of this leads to the chance we are given to discover the essence of what it means to be a human and the true meaning of work. A beautiful new existence awaits us where we focus on what makes us unique as a species, our curiosity, our consciousness, our dreams, our emotional intelligence, and our vision while the algorithms we have created assist us in the production and the execution of our authentic vision.”

– Pinar Seyhan Demirag, in the LinkedIn course “What is Generative AI?”

Maybe it’s unfair of me to use this specific example, because it couldn’t possibly be more effusive, and in other discussions on the same subject the text doesn’t become nearly this mystical and florid. But I was ambushed by this stuff today, so it’s top of mind– and it’s far from rare to find this kind of language used in the context of a work training course on any other topic (well, except DevOps, but even then…).

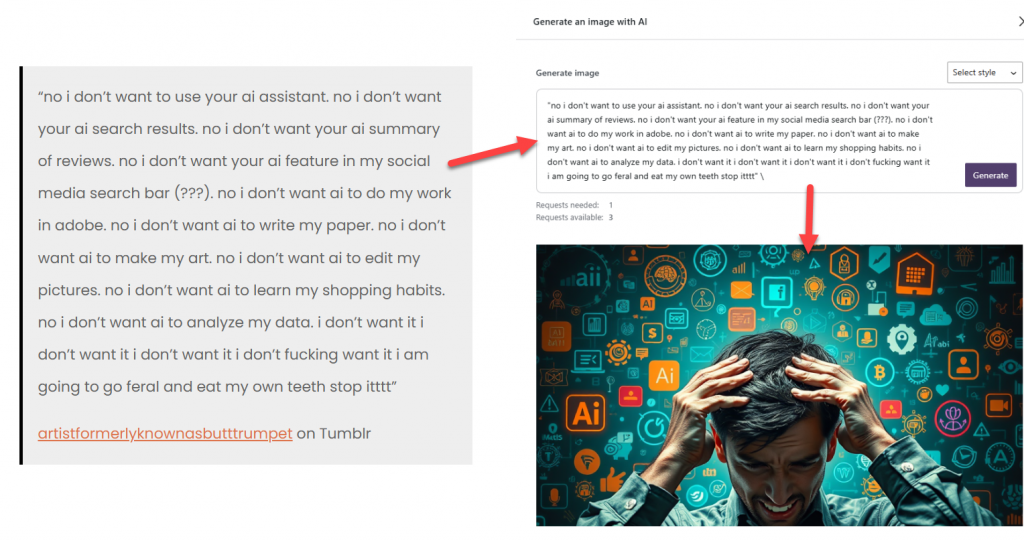

Yesterday I was looking for critical quotes about generative AI, and I found this one (below). When I inserted it into this blog post, I was prompted to generate an image with AI– which of course I did, to double down on the irony.

The quote:

“no i don’t want to use your ai assistant. no i don’t want your ai search results. no i don’t want your ai summary of reviews. no i don’t want your ai feature in my social media search bar (???). no i don’t want ai to do my work in adobe. no i don’t want ai to write my paper. no i don’t want ai to make my art. no i don’t want ai to edit my pictures. no i don’t want ai to learn my shopping habits. no i don’t want ai to analyze my data. i don’t want it i don’t want it i don’t want it i don’t fucking want it i am going to go feral and eat my own teeth stop itttt”

artistformerlyknownasbutttrumpet on Tumblr

I would love to see Pinar and artistformerlyknownasbutttrumpet, who now goes by “diz,” sit down and have this conversation in person.

Clearly diz is not talking about all of the technologies under the umbrella of Artificial Intelligence, but they are talking about various kinds of AI that mostly fall into the category of generative AI, the same category that Pinar is training me on.

One distinction that jumps out immediately is inclusivity vs. exclusivity– Pinar talks about generative AI as something “we created to assist us,” whereas diz refers to “your ai.” With the design of nearly any product, the people who actually use and experience the product are not the designers themselves. Even if they’re designers of some kind of AI, that doesn’t mean they are familiar with this kind of AI. So for most of us, most of the time, we’re not creating algorithms to assist us, but rather using (or actively avoiding) the algorithms created by someone else.

Pinar is literally talking about humanity as a species, and what it means to flourish as a species, whereas diz is carving out an exception to that grand vision by saying “Nope, not for me.”

If Pinar is the evangelist in this scenario, diz is the atheist.

Pinar characterizes generative AI as fundamentally a labor-saving device, enabling “large parts of the production process that are repetitive or can be computational” to be “facilitated by AI models.” But the word “computational” there belies the fact that the first computers were designed to do exactly this, long before AI models were a byte in some designer’s mind.

Computers began with code and programming with code, and the first device designed to perform such a task was actually an automated loom, designed and constructed in 1801 by Joseph-Marie Jacquard in Leon, France. The loom used punch cards to weave patterned silk, and part of a greater push by Napoleon for the French to compete more aggressively against Britain in automating tasks that would otherwise fall to humans.

But before the word “computer” was largely applied to devices, it referred to humans performing calculations. The first “human computer” was Barbara Canright, working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1939. During World War 2 she, along with dozens of other women by 1945, performed calculations to, for example, determine the trajectories of ballistics– largely without recognition. The title of an article on History.com neatly sums up how that went – When Computer Coding Was a ‘Woman’s’ Job: Computer programming used to be a ‘pink ghetto’ — so it was underpaid and undervalued.

And when computers were developed sufficiently, and stereotypes shifted along with it, programming became associated with men, with the occupation becoming hostile toward women.

Meanwhile, other forms of technology became known as the ideal “work-saving” devices for women.

“Mary used to be just the same,” this ad reads. “Tired out, nervy, from overwork, especially after the baby arrived. Then I bought her a VACTRIC. The difference was astonishing. Carpet cleaning no longer tires her. In fact, she likes it– with the VACTRIC.”

So the tedious and repetitive tasks of computing (as well as the innovation of programming, though that also wasn’t acclaimed or even acknowledged at the time) fell to women, until computers were developed (by men) to the point that they could perform those tasks more efficiently, at which point they replaced those women, who were still encouraged to save their own labor in terms of household chores by using technology that performed those chores more efficiently.

(Do you think they were encouraged to spend that time, saved by the gift of a VACTRIC from their husbands, to venture into computer programming? It doesn’t seem likely.)

The point here isn’t to rant about sexism throughout the history of technology– though I certainly could (some other time). The point is that we’ve had the chance to “discover the essence of what it means to be a human and the true meaning of work” since the invention of technology, and we keep discovering it, and the conclusions about those heady subjects have varied– and always will vary– depending on which individuals comprise the “we” in question.

The point is also that when a labor-saving device becomes sufficiently advanced, those performing the labor tend to eventually be usurped by it.

As diz notes, that doesn’t only happen with “production processes that are repetitive or can be computational,” although that could be better phrased as “production processes that are not repetitive or computational when performed by a human,” because computers work computationally, by default.

Computationally-generated examples of what humans produce non-computationally are really what we’re talking about, here. diz was specifically talking about incidences when those computationally-generated products are pushed on us– we who didn’t design them, and didn’t ask for them to “assist us with the execution of our authentic vision.”

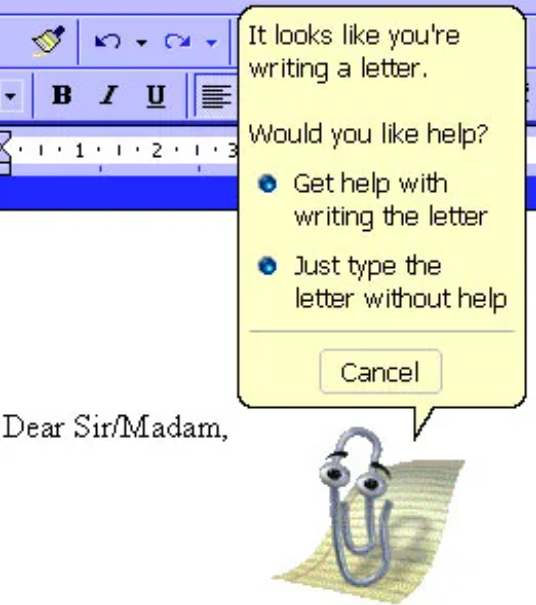

Personally I’m neither Team Pinar or Team diz, here, but I’m sympathetic to diz’s depiction of generative AI behaving more or less like Microsoft’s long-despised “office assistant” Clippy did in 1997-2001(ish).

According to the AI analytics company SAS,

Rather than using Natural Language Processing (NLP), Clippy’s actions were invoked by Bayesian algorithms that estimated the probability of a user wanting help based on specific actions. Clippy’s answers were rule based and templated from Microsoft’s knowledge base. Clippy seemed like the agent you would use when you were stuck on a problem, but the fact that he kept appearing on the screen in random situations added negativity to users’ actions. In total, Clippy violated design principles, social norms and process workflows.

You can find a much more through look into Clippy’s history in Whatever Happened to Clippy? on Youtube, which is fascinating in its own right, but also shows the broader context in which Clippy was developed as just one possible avatar of the office assistant functionality. (It’s also interesting to me a part of a look into the concept of chatbots in general, but again– that’s for another time.)

What I want to emphasize here is that diz’s complaint is sympathetic to people trying to “execute their authentic vision” because in our intuitive understanding, if a computer produces something, it isn’t authentic.

When the AI assistant offers to produce images and write prose for us, people who pride themselves on creating images and prose become suspicious and concerned for myriad reasons that primarily revolve around authenticity– matters of taste, matters of knowledge demonstration, matters of copyright, matters of accuracy on esoteric subjects (legal precedent, for example), and so on.

There’s a huge bandwagon of creatives and others making this same argument, and I’m not comfortable just hopping aboard, because the bandwagon never seems to clearly articulate what kind of AI it’s targeting. You can suss out that it’s generative AI, but the claims are broad and sweeping, and I’m not sure whether the people complaining that AI is bad because it makes fake art by stealing other people’s art also think that AI is bad when it makes fake medical analyses that are evaluated by medical professionals as being of higher quality and displaying more empathy than those from actual human doctors (also a subject to delve into further at another time).

Inauthenticity isn’t always bad (else artificial intelligence shouldn’t exist in the first place), but the closer you get to self-expression, the sketchier the incursion becomes. As AI becomes more adept at obscuring the “self” in the expression, I think it’s important to challenge narratives that treat it as an unqualified good.

And when it comes to the “true meaning of work,” and the potential of people finding their jobs replaced, and their work deemed unnecessary, it’s no longer a philosophical question.