This post is a continuation of Part I– if you haven’t read that yet, click this link.

The panel “Cartoonists’ Rights and the Free Speech Situation Facing the World” was moderated by Terry Anderson (again, acting director of Cartoonists’ Rights International) and included Ritu Gairola Khanduri (board member of CRNI), Ann Telnaes, Zunar, Pedro Molina, and Charles Brownstein (of the Comic Books Legal Defense Fund).

Ritu described the United Sketches Women Cartoonists International Award, and justification behind it– 5% of political cartoonists across the globe are women or nonbinary. (I submitted cartoons for this award. The deadline was September 15, and the judges are currently deliberating.)

Pedro told of the desperate state of political protest in Nicaragua, with newspaper offices and TV stations being raided and shut down. Pedro is a tireless advocate for independent journalism, even at great risk to himself, and that risk was evident in his talk. You can read more about him in this interview with the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas or on his own site.

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar told stories of his repeated arrests in that country that were both horrific and hilarious, such as how once the police chief ordered his arrest by tweet, and Zunar’s cartoons for the next year or so all featured some tiny depiction of the police chief tweeting on his phone. Zunar is known for photos of him smiling in handcuffs during these arrests, though the risk has been significant considering that in 2015 he faced up to 43 years in prison for criticizing the Malaysian government. You can read more about Zunar at his site, where you can also find his new book recounting his experiences, Fight Through Cartoons.

Ann described the fallout in 2015 when she published a cartoon mocking Ted Cruz for using his daughters to promote his presidential campaign. You can see the cartoon here, as well as read the AAEC and CRNI reactions to the Washington Post’s decision to pull the cartoon after receiving complaints about it. Telnaes depicted Cruz’s daughters as performing monkeys, which (it seems painfully obvious to me) was not actually an attack on his daughters, but on Cruz for using them as props– something politicians do all of the time, and is off-putting every time and completely deserving of criticism. The title of the cartoon was literally “Ted Cruz uses his kids as political props.”

But after Cruz himself complained, and Marco Rubio joined him, the Post took the cartoon down and replaced it with an editor’s note (visible at the above link). That didn’t end things for Ann, however– she received a torrent of messages via email and social media that were abusive and sexist. To convey the nature of these messages, she played a video of similar harassment received by sports reporters Sarah Spain and Julie DiCaro. It is of course a good thing that the Washington Post didn’t react to complaints about a political cartoon in the same way that the New York Times would do four years later, but their capitulation in taking the cartoon down almost certainly enabled the harassment against Ann. That of course didn’t remove the ability of people to see the cartoon– all it did was tacitly agree, apparently without any consultation at all with Ann herself, that her cartoon was inappropriate.

Charles Brownstein described the power of social media influences in regulating content related to social justice issues. Charles is executive director of the Comic Books Legal Defense Fund.

The next panel was titled “The Legacy of Trump,” discussing the impact of Trump’s presidency on political cartooning during his tenure and anticipated effects in the future. The moderator for this panel was Mike “Comic Strip of the Day” Peterson, and the panelists were Patrick Chappatte, Nick Anderson, and Nancy Ohanion.

The next panel was titled “The Legacy of Trump,” discussing the impact of Trump’s presidency on political cartooning during his tenure and anticipated effects in the future. The moderator for this panel was Mike “Comic Strip of the Day” Peterson, and the panelists were Patrick Chappatte, Nick Anderson, and Nancy Ohanion.

This was more of a free-flowing discussion than the previous panel. If you read part I of this post or my previous post “On the death, dearth, and demographics of political cartoons,” then you know who Patrick Chappatte is. You may also recall that Nick Anderson is the founder of Counterpoint. He attended this meeting with his wife Angel, who I got to meet at the Billy Ireland museum and talk about life in Texas, how the two of them came to settle in Houston, and much bodices cost at the Texas Renaissance Festival, the largest (to my knowledge) ren faire in the country that takes place yearly in November just outside of Houston. (Answer: Yes, bodices cost a lot, but they’re kind of a ren faire staple and well worth the investment if you’re a ren faire junkie like I used to be.)

Anyway, Counterpoint! The condensed version of the origin of Counterpoint is that Nick Anderson, a Pulitzer Prize winner, was himself subject to the ongoing purge of political cartoonists, having been let go at the Houston Chronicle after eleven years of cartooning in 2017. Nick saw Rob Rogers undergo the same experience in 2018, recognized and was alarmed by the trend, and wrote up a statement for the AAEC board. Pat Bagley (Salt Lake Tribune, also at the AAEC meeting this time but unfortunately I didn’t get the chance to meet him), was president at the time and apparently brought the piece to the attention of Jake Tapper (occasional cartoonist himself) and therefore CNN, who published the piece on their Opinion page.

There it was read by Vivek Garipalli, venture capitalist and co-founder of Clover Health, who orchestrated a meeting of minds with Nick that resulted in the creation of a cartoon email newsletter with a theme of dialogue between cartoons and cartoonists with opposing viewpoints known as Counterpoint. Currently I believe subscribership is at something like 130,000, and the plan is to become self-sustaining with advertiser support in the future. Newsletters are emailed free to subscribers twice a week.

I’d gotten the chance to speak with Nancy Ohanion when we were tabling on the vendor floor, and learned that while she’d been doing political cartoons for decades (since before I was born) and is syndicated, she’d been doing all of it, including a full-time career in advertising, on her own until recently. Since I’d never so much as spoken to another cartoonist prior to this meeting, it was amazing and gratifying to talk to her about the community aspect of AAEC, and what it could become in the future.

In this panel, she noted that Donald Trump is not some kind of singular force in modern American politics– that he’s more like a symptom of a disease that leads people to seriously bring up the word “sedition” when talking about political dissent, that makes calling someone a “member of the media” a near-slur, and generally speaking makes the country a more dangerous place for the kind of critique and mockery that are essential, indispensable even, to editorial cartooning. And, as Nancy hastened to add, even when (please don’t say “if”) Trump goes away, this national attitude will not. So we need to decide how to respond to it. Post haste.

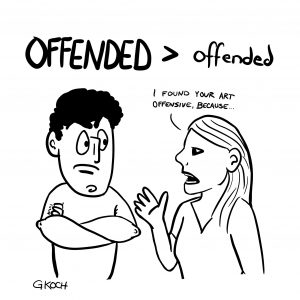

This panel also contained a lot of discussion about “offense” and its impact on cartooning, and I found myself pulling my iPad out of my bag and doodling a cartoon of my own as I listened.

Because we should never forget, in the discussion about how oppressive offended people can be, that offense is not itself oppressive. Offense is simply the feeling of being bothered by something that seems to insult you, or someone you care about, or a principle that you hold dear. I’ve seen artists of many kinds– comedians, musicians, cartoonists, and others– react to criticism in really ugly ways. And it’s not entirely their fault, because we do live in a country, in a world, where offending the wrong people can be career-ending. Sometimes life-ending. But that isn’t the fault of the offended, generally. You cannot simultaneously say that cartoonists should be free to push boundaries (which I forever will maintain that they should), and also raise a fuss when people react to seeing those boundaries pushed. Nobody gets to be infallible. Everybody screws up sometimes.

One of my favorite quotes comes from Elbert Hubbard: “To avoid criticism, say nothing, do nothing, be nothing.” I do not, however, interpret this quote to mean that we should resent criticism, avoid it, or ignore it. Rather, we should distinguish it from harassment, attacks, abuse, trolling, etc. which are not criticism, and once we have identified it as authentic and made in good faith, we should wrestle with it. Sit with it. Consider it. That’s how we become better artists, and better people.

And there is of course a corresponding obligation for critics, to make their critiques in good faith, exercise charity, and recognize that even legitimately offensive speech is not necessarily an occasion to go beyond criticism into advocacy for more punitive measures (or, in case it needs to be said, harassment and death threats).

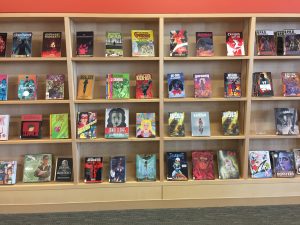

Since I already blathered on at length about this subject in the previous post, I will cease blathering here and show you this shelf at the metropolitan library next to the vendor floor. See that book on the lowest shelf on the left, Drawn & Quarterly: Twenty-five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels? I must have that book. But no, in case you’re wondering, I did not grab it and run from the library. I have more self-restraint than that.

Since I already blathered on at length about this subject in the previous post, I will cease blathering here and show you this shelf at the metropolitan library next to the vendor floor. See that book on the lowest shelf on the left, Drawn & Quarterly: Twenty-five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels? I must have that book. But no, in case you’re wondering, I did not grab it and run from the library. I have more self-restraint than that.

That Saturday evening of Day 3 was the final evening for many of us. We converged on Hotel LeVeque for a reception and the AAEC awards, much of which I covered in Part I. In addition to the CNRI awards, however, there were some other highly important honors. Before the awards began, I briefly got to meet Liza Donnelly, cartoonist for the New Yorker (okay, actually meet again because I’d met her earlier in the day along with talented David G. Brown and not realized it), and enthuse over a piece she’d written in 2017 for Medium entitled Editorial Cartooning, Then and Now, which was excellent and really should’ve been part of the “Legacy of Trump” discussion earlier in the day.

The Rex Babin Award for local cartooning was presented by Jack Ohman to Kal Kallaugher, with Nate Beeler as finalist. Nate was a previous winner of the Locher Award, which you may recall was this year given to Chelsea Saunders.

The Ink Bottle Award for outstanding service to the AAEC and to the profession generally, was given to the very deserving Ann Telnaes. Ann’s acceptance of the award was predicated on her being able to share it with Signe Wilkinson, who also contributed immensely to this year’s meeting organization. I love Signe’s work and very much regretted not being able to meet her this year– circumstances prevented her from being there to accept the award along with Ann.

As a new member I hung back for most of this ceremony, delighted and touched by the camaraderie but reluctant to insert myself. I gravitated to fellow new member the immensely talented Tamara Knoss, with whom I’d had dinner the previous evening, along with NC cartoonist Ross Gosse and “Mr. Fish” Dwayne Booth, who had unfortunately been compelled to head back to New York by this time.

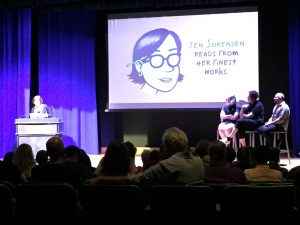

The evening was not nearly over with the reception, however– from there we proceeded to the Columbus College of Art and Design’s Canzani Auditorium for the Save the Nib event!

I don’t know that any of us truly knew what we were in for with this event. Seated next to Cullum Rogers, with Ann Telnaes and J.P. “Jape” Trostle behind me, AAEC members and college students throughout the audience, we witnessed what turned out to be a sort of live-action play/testimonial/Powerpoint presentation/tribute/fundraiser/stand-up act/Q&A performed by Nib editor Matt Bors, deputy editor Eleri Harris, associate editor Matt Lubchansky, contributor Chelsea Saunders, contributor Jen Sorenson, contributor Rob Rogers, and contributor Dan “Tom Tomorrow” Perkins.

Matt Bors, Matt Lubchansky, and Eleri Harris first told us the history of The Nib, its rocky excursion as a publication, gaining and then losing funding, repeatedly, until the most recent upheaval when First Look Media bailed and The Nib became Matt Bors’s reader-funded project earlier this year. They talked about story arcs in their comics, their venture into animation, and the emergence of themes such as “Gotcha Guy” and depictions of Trump as a quasi-“Immortan Joe” character in their imagined apocalyptic wasteland scenario in both comics and animated cartoons.

If anything became clear in the course of this presentation it’s that The Nib has been WORK. Blood, sweat, tears, and long periods without health insurance for everyone involved. This was, and is, a labor of love– that much is more than obvious.

They were dedicated to keeping the mood of the presentation light, in spite of the dire stakes that came through in the retelling, but things authentically lightened up even more when we proceeded into Chelsea Saunders, Rob Rogers, Jen Sorensen, and Dan Perkins each in turn describing their personal histories in cartooning and literally narrating selections of their comics. Rob Rogers read and commented on the entire comic he did on being fired from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette for criticizing Trump for The Nib, which I’m sure was exponentially more fun to rehash as a result of his cartoon artistry than it was to go through as an experience.

That’s what cartooning can do– frame an experience as a story, told by a storyteller, for an audience viewing and listening to the story as much as for the teller him or herself. That’s something that all cartoons have in common, fiction or non-fiction, “political” or otherwise.

That is, it turns out, the ultimate reason why I don’t think political cartooning will go away– we humans will never get tired of being told stories about politics, about the exertion of power by some people over other people, mocking the “jerks in power” and sticking up for the little guy, the underdog.

I can’t say I know the future of these underdog stories, and it would be hubris to claim otherwise. But I can say that I’m invested in the telling of these stories, and probably will be for the rest of my life. That’s why I joined the AAEC. If you’re a cartoonist with a passion for politics who happened to come across this post, considering joining up. Then we can see, and perhaps play our own role in determining, what the outcome of this story will be.