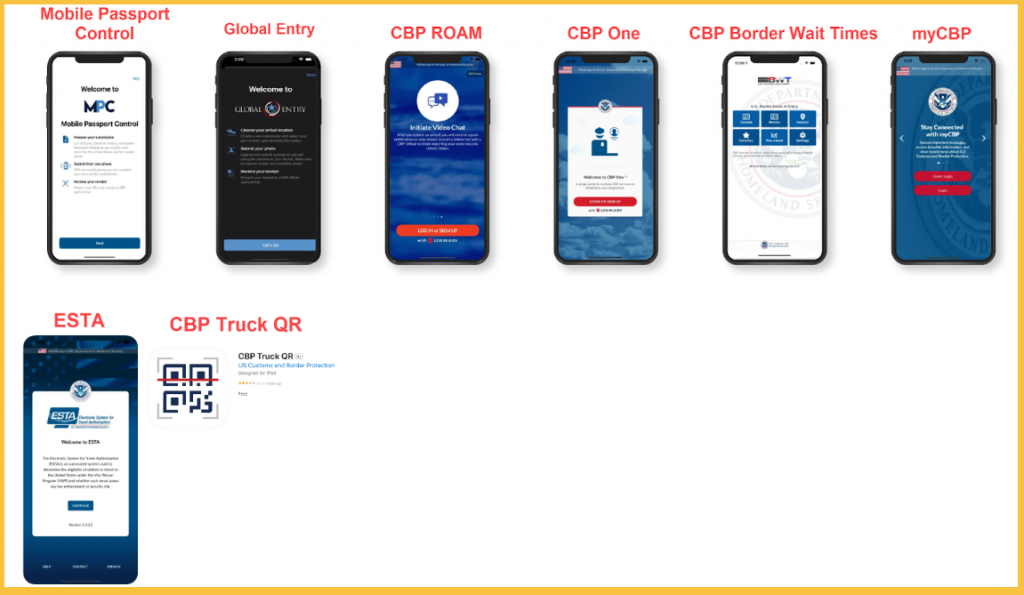

In August of 2018, in light of the growing number of apps under Customs and Border Protection, the agency’s Office of Field Operations (OFO) announced that it would develop the CBP One mobile application in collaboration with the Office of Information Technology (OIT).

The app would prevent the confusion that comes with travelers needing to access multiple apps to access services by functioning as a hub for all services, e.g. cruising licenses for pleasure boating, Form I-94 application and management, inspections of cargo, checking border wait times, submitting flight and bus manifests– hence the name “CBP One.”

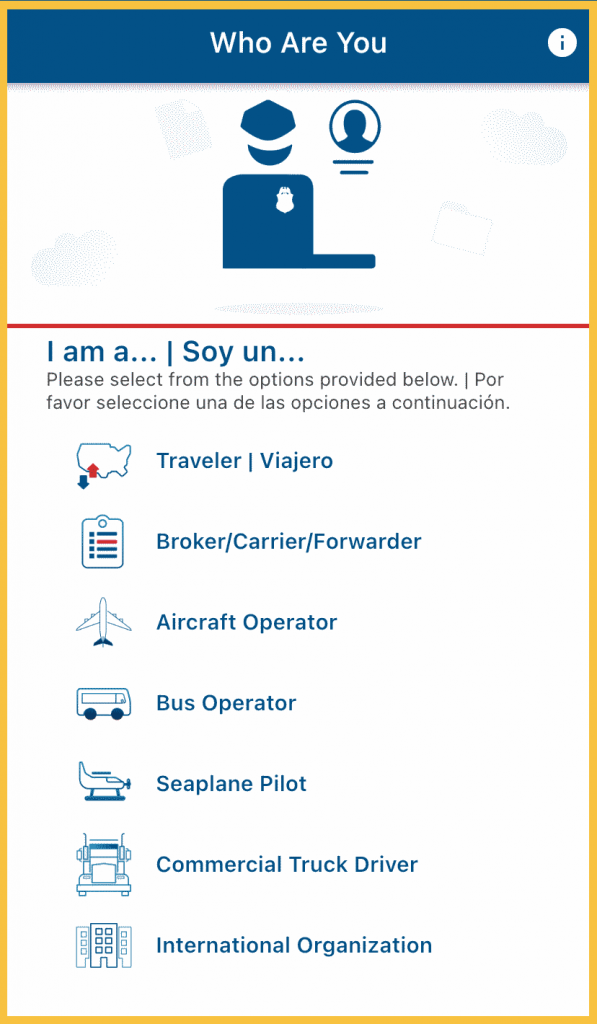

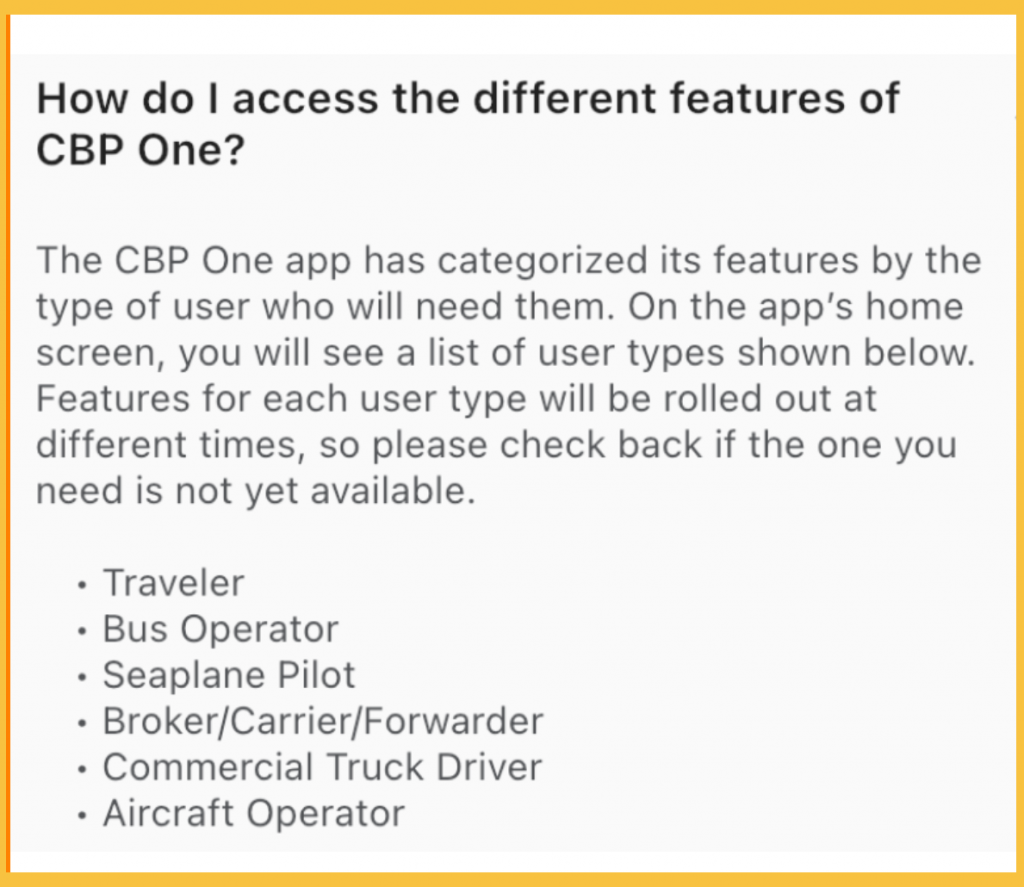

These services would be incorporated over time, according to a roadmap that plotted them out over the next few years, and would become accessible to each user type by asking them a series of intuitive questions and guiding them to the services they need.

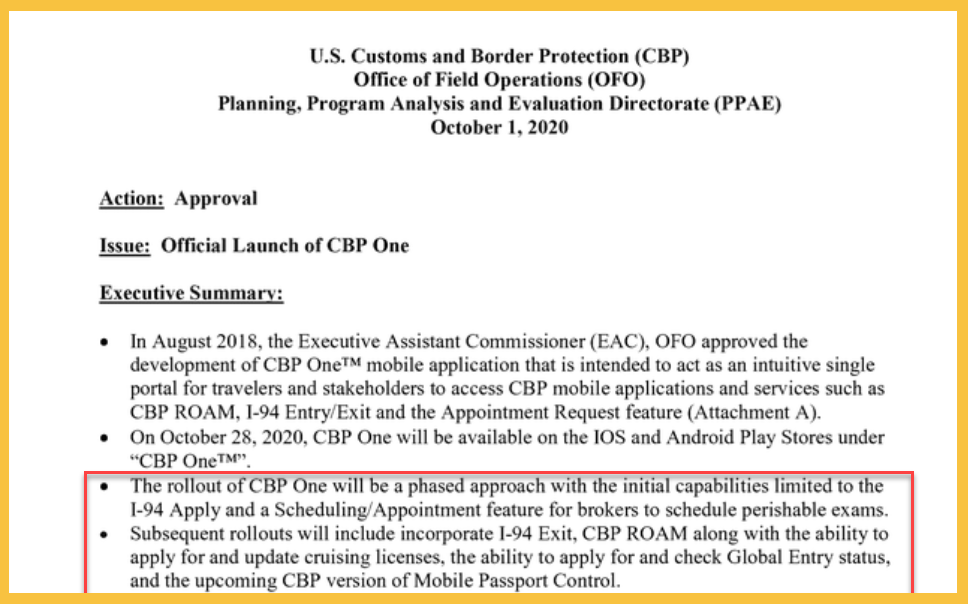

CBP One launched on October 28, 2020 with few capabilities and high expectations that more would be rolling out soon.

However, gathering information from hundreds of thousands of migrants, and using it to process them at the border. was not one of those.

This review shows the following:

- CBP One’s development diverged in audience and focus almost immediately upon launch, if not prior.

- And yet, CBP One’s user interface still reflects that original intended usage and user groups– even though many of those usages or user groups never made it into the app.

- CBP One’s documentation is largely intended for internal audiences, and in some cases the public– not migrants using the app.

- What information is made available to the public, and to migrants specifically, obscures how the app actually works, and how it gathers and uses information provided by users of the app.

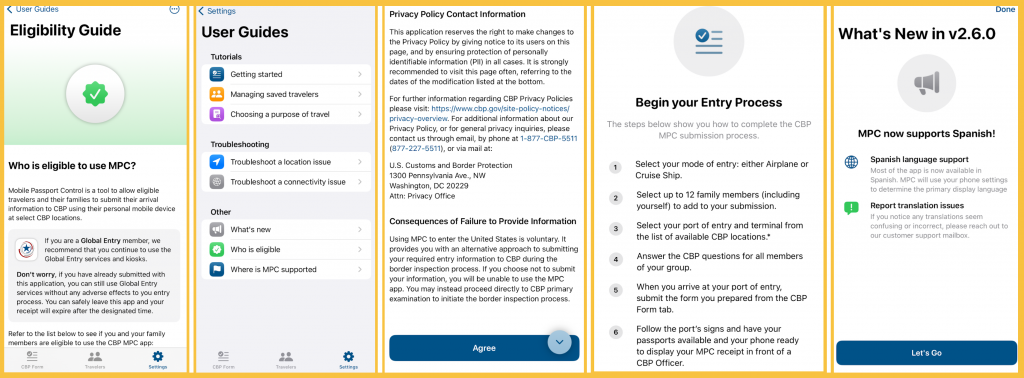

- It doesn’t have to be this way– a look at the Mobile Passport Control, developed originally by CBP in collaboration with Airside in 2013, belies the fact that a superior user experience is possible, and the current UX of CBP One is a choice made by its developers.

- CBP One expedites the transmission of a migrant’s information to CBP, but the only benefit here appears to be for CBP.

- The requirement to use an app to enter the country lawfully is not only arguably a violation of their rights as asylum seekers, but the inferior functionality of the app and lack of critical information in easy-to-access locations for migrants reveal a fundamental lack of respect for basic human dignity and equality.

Objectives:

Explain what the CBP One app was supposed to be vs. what it became

- Review the technology used

- Walk through the documentation

- Evaluate criticisms of the app

- Show where major events occurred on a timeline

A word about terminology:

Certain terms are used interchangeably in DHS and other documentation concerning CBP One, so here’s some clarification on how to understand those terms:

- International Organizations (IOs) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are used interchangeably in DHS documentation. Generally, these are organizations approved by the Mexican government to assist migrants in Mexico, who effectively do unpaid work that the DHS relies upon. They give migrants access to basic necessities like food, shelter, clean water, electricity, and education. Before CBP One, they communicated with Border Patrol about migrants in advance of those migrants approaching the border, and when CBP One was modified with the expectation of IOs using the app on behalf of migrants in 2021, CBP provided them with training on doing so.

- User roles/personas/user types are used interchangeably in CBP documentation.

- Likewise services/capabilities/features.

- Facial recognition technology/facial analysis technology/facial comparison technology, AI versions of any of these, and liveness detection will be referenced interchangeably as “FRT” for the most part, except when it’s necessary to disambiguate them.

- The term “migrant” is defined in the DHS glossary as “a person who leaves his/her country of origin to seek temporary or permanent residence in another country.” That’s how the term is used here, and it includes asylum seekers and refugees.

What the CBP One app was supposed to be vs. what it became

Overview

CBP One’s original vision, as you can see in this memo, was to serve both travelers and private commercial interests, both of whom have a need to access CBP services.

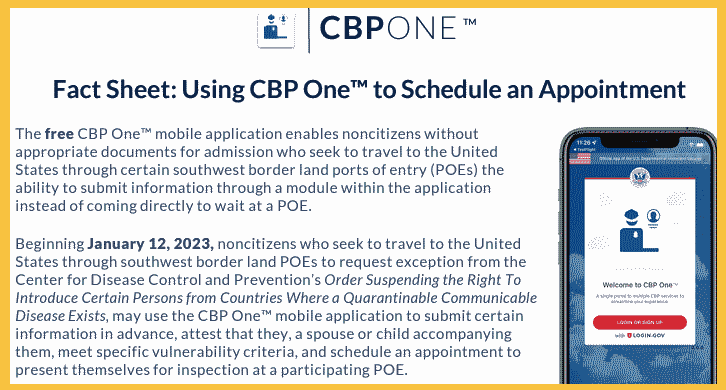

But as soon as the app launched– perhaps even before then– its functionality changed to suit unanticipated needs, including gathering large amounts of data from a vast population of migrants, so that the migrants could request appointments at the border for inspection and legal entry into the United States.

Note: This memo was obtained via FOIA request by the American Immigration Council (click here to see the document). Internal documentation in this write-up is mostly pulled from that source.

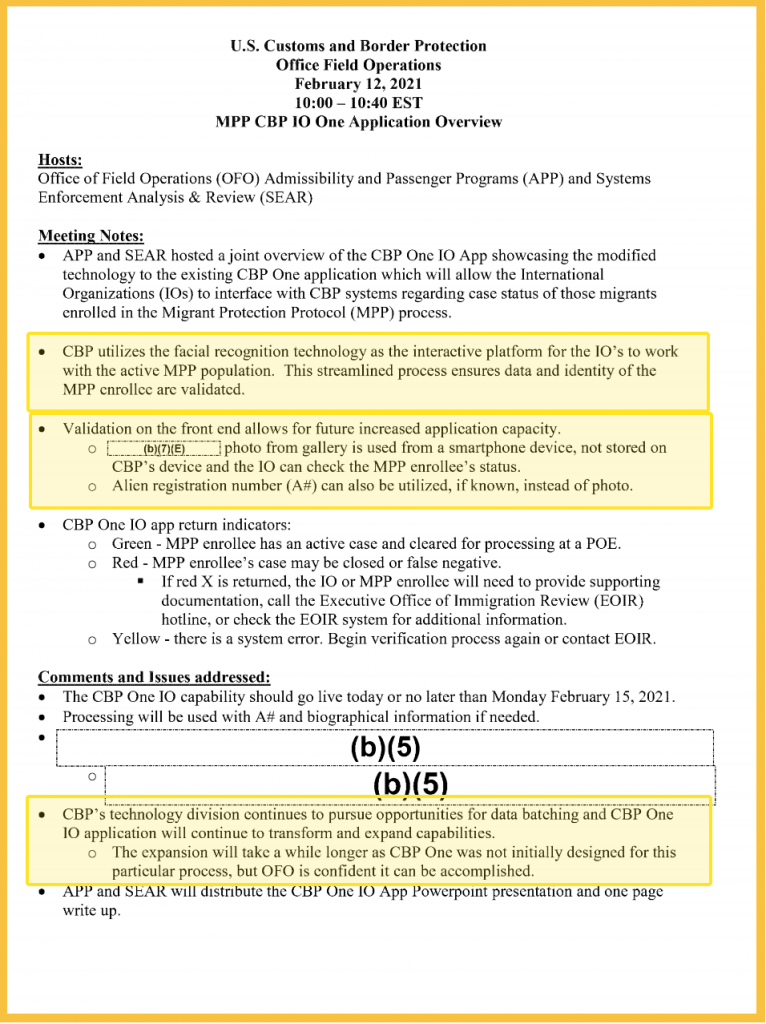

The app was “not initially designed for this particular process,” according to notes from a meeting in February 2021. By this point, its developers were already deviating from that original vision.

They were incorporating AI facial recognition technology, which probably would’ve been incorporated into the app regardless if it had gone on to incorporate Trusted Traveler programs as planned, but instead, FRT was used in the app to compare migrants against DHS databases and keep their images on file for future use.

The app’s user based shifted to accommodate IO/NGO staff who used it to check migrant enrollment in the Migrant Protection Protocols and submit information about migrants in advance of their appointments at the border.

A year later it would change again, to accommodate those migrants using CBP One to submit information on their own and schedule their own appointments.

Because of these external needs to use the app in ways that diverged from its original purpose, its usage changed dramatically. As a consequence of that, its functionality changed as well.

Some of the public-facing documentation reflects that shift in usage, but some very important parts of it don’t. The design of the app was forced to change, but most public-facing documentation doesn’t reflect that. Statements about what the app is for and how it’s used, both within the app and in most external documentation specific to CBP One, also don’t reflect that.

My goal here is to show that, and suggest reasons why.

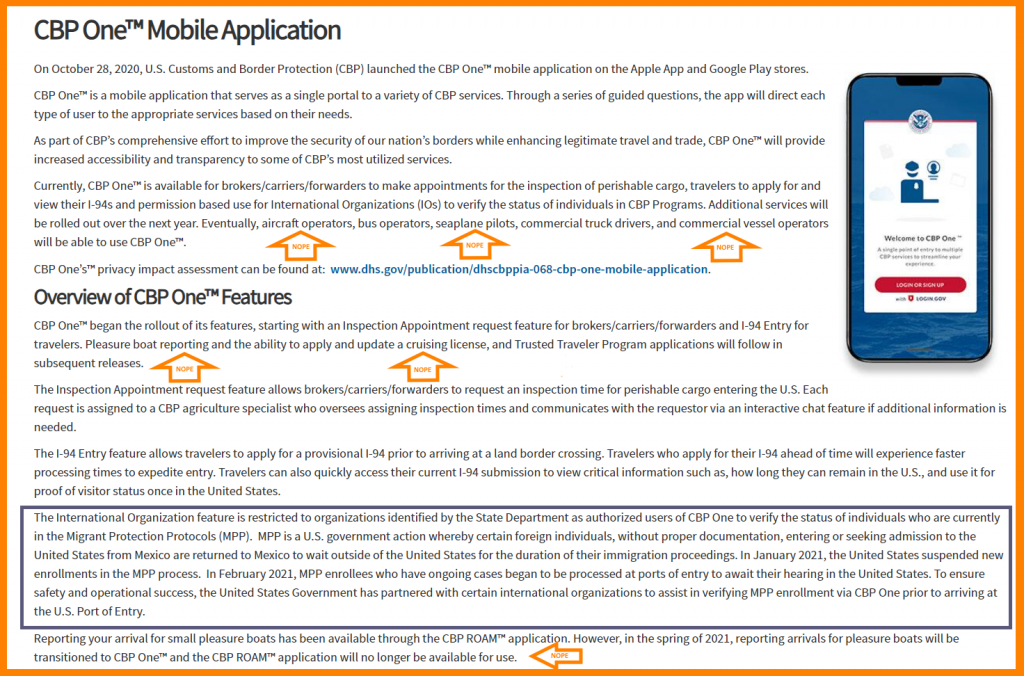

User roles and services/capabilities

One choice made in CBP One’s design was that the app would display all anticipated user types and services from the beginning, and gradually they would become accessible within the app. Until that point, clicking on those user types and services would trigger a pop-up message saying “Coming Soon. This feature is coming soon. Additional services will be rolled out over the next year.”

As a result, it can be difficult to tell which user types and services were available at any particular point in the app’s development. You can’t, after all, time travel back to any of those points and try the app out for yourself, so I’m forced to discern the app’s functionalities based on the following:

- Reports from users of the app at different times in its development

- Statements made by CBP/DHS

- Changes in the law/policy that required changes in the app

For this section, I’ll focus on services known to be available at launch.

- The Broker/Carrier/Forwarder role could schedule inspections of cargo prior to crossing the border, an idea pitched at a “shark tank” event at the Miami Field Office in 2018 and pilot tested in 2020.

- Land and Air Travelers could access the Form I-94 website from the app. The is needed by most international travelers to the United States, and it’s used to track entrance to the country and exit from it. Through the app, a traveler could apply for the form and then use it to access their travel history, prove their visitor status. Land travelers could use it to apply for a provisional Form I-94 (it’s generally automatically for air travelers).

Not long after, Air Travelers could apply for membership in one of the Trusted Traveler programs which expedite screening and other processes of international travel for pre-vetted American citizens. They could also Request Inspection of certain items like hunting trophies.

Bus Operator could Submit a Manifest and Check Border Wait Times by checking the Border Wait Times site within the app, where they would be (and are still) prompted to get the CBP Border Wait Times app.

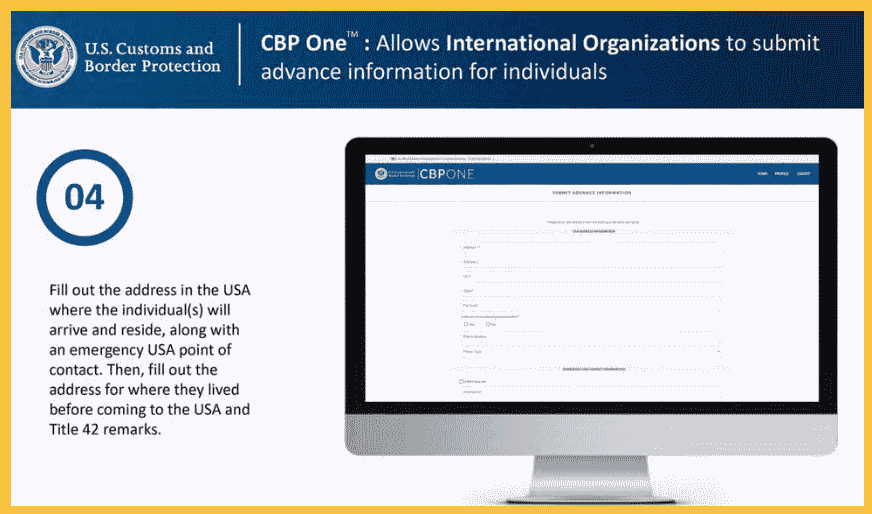

Services added in 2021 for the International Organization role to assist migrants:

- International Organization > Check Case Status

- International Organization > Submit Advance Information

Subsequently, migrants could access these services themselves:

- Air Traveler > Advance Traveler Authorization: “Request authorization for non-United States citizens intending to travel to the United States via flight. This action is only available to travelers following the approval of their supporters on Form I-134A through the USCIS.”

- Land Traveler > Submit Advance Information: “Submit your information before your arrival to a southwest Port of Entry.”

Additionally there’s a TSA role, hidden to anyone who doesn’t use a TSA email address to log in, allowing TSA supervisors to take a photo of asylum seekers enrolled in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program using facial recognition technology (FRT) to verify their enrollment and allow them to travel within the country.

A bend in the roadmap

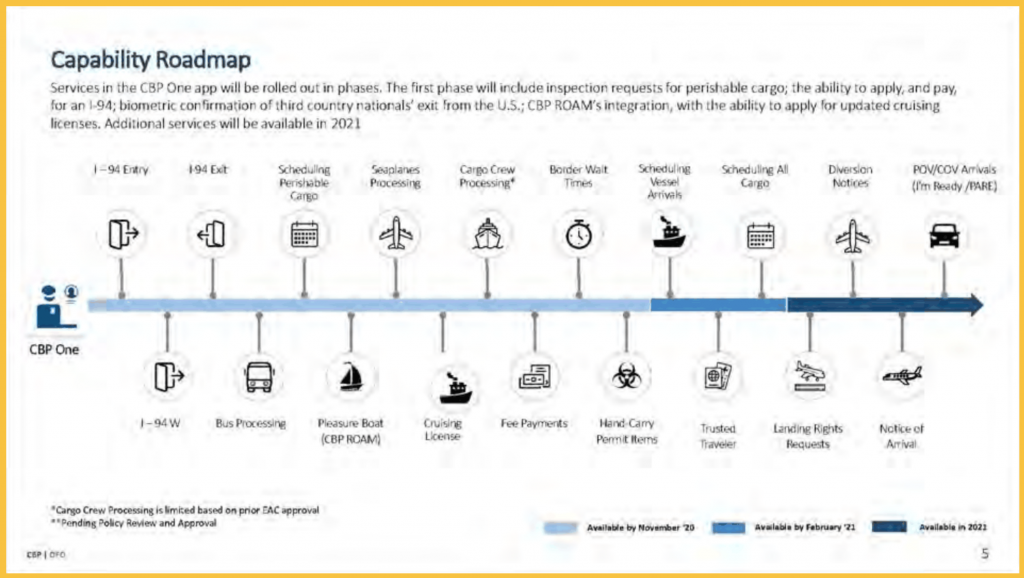

CBP One has changed significantly over the time since launch, diverging from the capabilities planned on this roadmap from October, 2020.

Apologies for the blurriness (it’s from the FOIA docs), but you should be able to see that I-94, Bus Processing, Scheduling Perishable Cargo, Pleasure Boat (CBP ROAM), Seaplanes Processing, Cruising License, Cargo Crew Processing, Fee Payments, Border Wait Times, and Hand-Carry Permit Items were all to be added by November of 2020. (Launch day was, remember, October 28!)

By February of 2021 the features would include Scheduling Vessel Arrivals, Trusted Traveler programs (not just signing up, but doing everything you currently do in the Global Entry app, for example), and Scheduling All Cargo.

2022 would bring Landing Rights Requests, Diversion Notices, Notice of Arrival, and POV/COV (I’m Ready/PARE), which refers to Ready Lanes at land border crossings. You can get expedited processing and across the border faster if you have one of several RFID chip-enabled ID cards.

It looks like CBP One got about as far as Perishable Cargo before that road diverged at the beginning of 2021.

The UI as intended

I think the original premise for navigating the app is pretty intuitive in itself, as a way to shortcut a user to which services apply to them and away from those that don’t, even if it means some repetition where different types of users need the same service (e.g. I-94 travel history), so you’ll see the same option listed for two different user roles. That’s intuitive given the intended audiences for the app– American companies/citizens, who need to interact with Customs services to comply with regulations regarding commercial shipping and/or international travel, and documented international travelers who need to access that documentation quickly.

It could’ve been done differently and be even more intuitive, though, based on how large the audience is for one service or another. E.g. if 75% of your audience needs Form I-94 services, it would make more sense to put that on the home menu rather than burying it behind Traveler > Land or Traveler > Air (or Traveler > Sea, but that’s “Coming Soon.”) That would require knowing how large your audiences are for different features, but those stats could be pulled from the existing apps/web pages where they’re currently accessing the features. And of course, it would likely require modifying the user interface as you go.

It’s difficult to go beyond that first impression, however, because that’s all it is– a first impression. That home screen is the face of a different app than the one CBP One would turn out to be.

6 very simplified, chronological user guides to CBP One

Why put user guides here, when they exist on the CBP One website? And why six of them?

To show how the user experience changed from February of 2021 (when IOs first started using the app) onward, I’ve written up some very abbreviated user guides reflecting how the app was used with each major change over time– from the migrant’s point of view, because they are The User.

User Guide 1: February, 2021 (MPP Check Case Status)

In December of 2018, the Trump administration announced the so-called Migration Protection Protocols, and the program went into effect in January of 2021. The MPP or “Remain in Mexico” program allowed DHS to send migrants to Mexico upon their arrival at the border and prevent them “clustering” at the border while waiting for their hearings. At this time, the International Organization user role in CBP one allowed staff from those organizations to identify migrants who were enrolled in the program.

You made it to the border, but they gave you a piece of paper and put you back on a bus to Mexico, where you joined 70,000 other migrants given a court hearing and a notice to appear, then sent away with no real plan to make it back in time for that hearing. You’ve been through hell in Mexico, but CBP officers weren’t asking about that. To request asylum at the border, you’d have had to affirmatively assert that you’re afraid of being sent back, and only then you might’ve gotten referred to a UCSIS asylum officer.

That piece of paper they gave you has your A-number on it, and you’re so grateful that your paperwork wasn’t stolen (and of course that you weren’t one of the 1,544 cases of rape, kidnapping, assault, and other violence committed against migrants sent back under MPP.

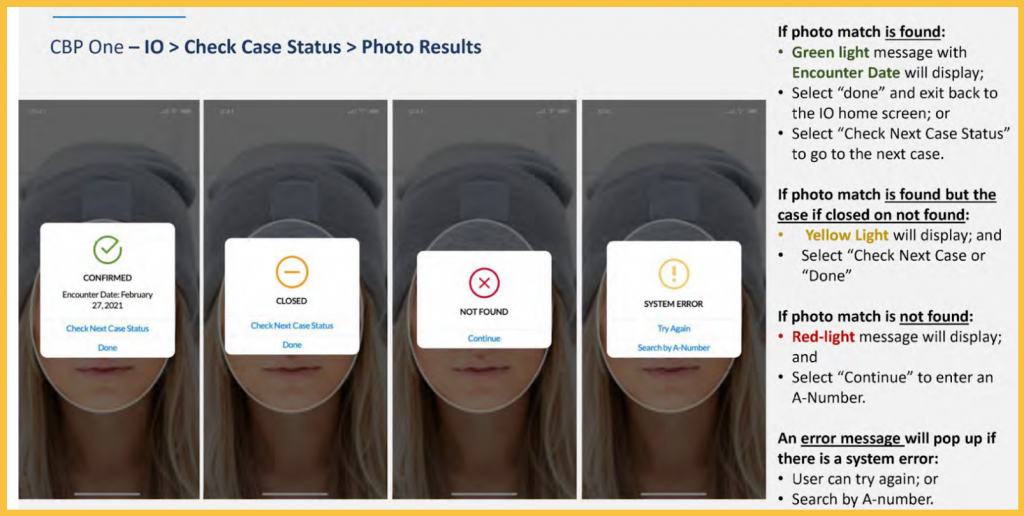

That number is one of the ways a kind woman from, say, the Keynote Border Initiative is able to look you up using an app on her phone. She needs to send off the right information that identifies you in an Immigration and Custom Enforcement, or ICE database called the Migrant Protection Protocols Immigration Enforcement Database, or MPP IED.

If she can verify that you have a hearing pending, you can go back to the border to attend it (if you don’t, your case is thrown out for failure to appear). Turns out she has to use your A-number to do that, because the photos she takes aren’t being accepted. But finally, you’re confirmed as enrolled with a case pending.

This screenshot is from a Powerpoint presentation given to IOs in early February. It was never provided to the public, even when migrants started using the app directly.

User Guide 2: March, 2021 (Title 42 Submit Advance Information)

To streamline the processing of undocumented individuals who may potentially be excepted from the CDC Order, CBP is relying on partnerships with certain International Organizations/NGOs. International Organizations/NGOs will identify undocumented individuals that are potentially excepted from the CDC Order on humanitarian grounds. . . .The manual input of data into USEC by CBPOs is a time-consuming process. The advance collection enables CBPOs to import the information collected by CBP One™ directly into a Unified Secondary event, which reduces the need for manual data entry and improves case processing efficiencies.

PIA, Unified Secondary System: Advance Information from Certain Undocumented Individuals DHS Reference No. DHS/CBP/PIA-067(a)

Yours was one of the 1.8 million expulsions from the border under an emergency implementation of a U.S. health law, Section 265 of U.S. Code Title 42, otherwise known simply as Title 42, which went into effect on March 20, 2021.

IOs have been training on using the CBP One app to take information about you, such as the standard names, dates, birthplaces, etc. but also information about your parents, the address where you lived before coming to the US (which address, exactly?) and other more specific information.

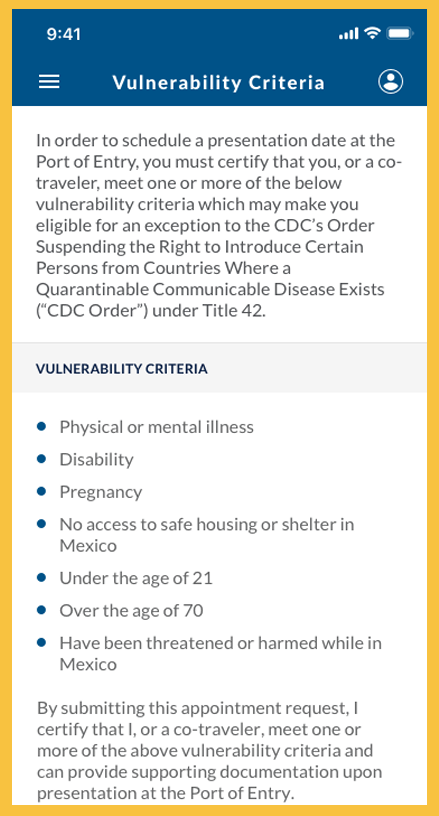

They’ll submit this information about you along with a statement attesting that you fit one or more of the vulnerability criteria that would merit exemption from Title 42, under which there is no claiming asylum– CBP stopped processing that asylum requests this month, expelling over 215,000 parents and children together who were asylum seekers.

But at least a teacher from the Sidewalk School helping your kids learn English is able to submit this statement on your behalf. You fit at least two or three of the criteria, so maybe you have a shot? Guess we’ll find out.

User Guide 3: April 25, 2022 (Ukrainian Direct Submit Advance Information)

Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s invasion could come to to the U.S. through the Uniting for Ukraine humanitarian parole program, i.e. be accepted into the U.S. for a period of two years to live and work lawfully, provided they pass a background check and have a financial sponsor who applied for a Form I-134A on their behalf.

- Go to Login.gov, “the public’s one account for government,” and create login credentials for yourself to use in CBP One.

- Log in to the app and select Traveler, then Air.

- On the Air Traveler screen, select Advance Traveler Authorization: “Request authorization for non-United States citizens intending to travel to the United States via flight. This action is only available to travelers following the approval of their supporters on Form I-134A through the USCIS.”

- On your first time using the app, a pop-up will say that your profile is missing information. Hopefully your English is good enough to carry you through this, because that and Spanish are the only options.

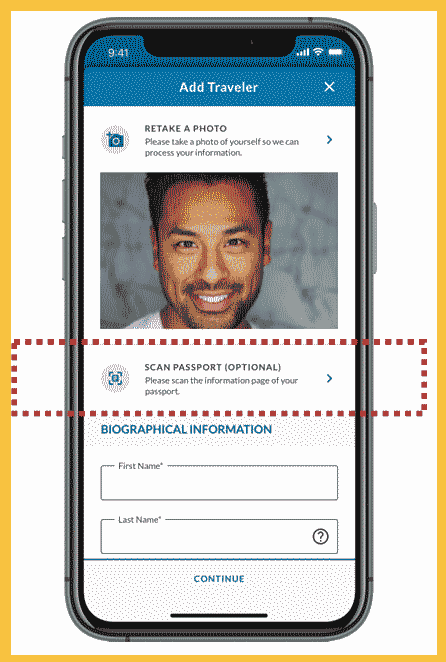

- Facial Photograph

- Photo obtained from the passport or Chip on ePassport, where available

- Alien Registration Number

- First and Last Name

- Date of Birth

- Passport Number

User Guide 4: January 5, 2023 (CHNV Direct Submit Advance Information)

On January 5, 2023, the Biden administration announced a humanitarian parole program for nationals of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela (CHNV). Up to 30,000 refugees in the CHNV program would be accepted into the U.S. each month for a period of two years to live and work lawfully, provided they pass a background check and have a financial sponsor who applied for a Form I-134A on their behalf.

Nationals of these countries could use CBP One to submit their information in advance, but if they attempted to enter the United States without using the app and/or somewhere outside a point of entry, they would be expelled. With the opportunity to enter as a refugee, CHNV nationals largely lost their chances at applying for asylum, and Mexico made an agreement with the U.S. to allow up to 30,000 asylum seekers to be expelled to Mexico each month– despite not being from Mexico.

See user guide 3 for instructions, but if you’ll be arriving by land entry, use CBP One to make the appointment.

User Guide 5: January 12, 2023 (Title 42 Direct Submit):

Anyone can use the app now to submit their information and attest that they fit the vulnerability criteria to be exempt from Title 42. But now IOs aren’t instructed to help you– you have to do it yourself, and there is no guide to using the app anywhere. Not within the app, and at this time there isn’t even a website.

- Go to Login.gov, “the public’s one account for government,” and create login credentials for yourself to use in CBP One.

- Log in to the app and select Traveler, then Land.

- Select Submit Advance Information | Enviar Información Anticipada, then fill out your profile: Name, Date of Birth, Phone Numbers, U.S. Address, Foreign Addresses, Nationality, Employment history, Travel History, Emergency Contact Information, Family Information, Marital information, Gender, Height, Weight, and Eye color.

- Take a photo of yourself and upload it.

- Confirm that you meet one or more of the vulnerability criteria and can provide supporting documentation, and hope for the best.

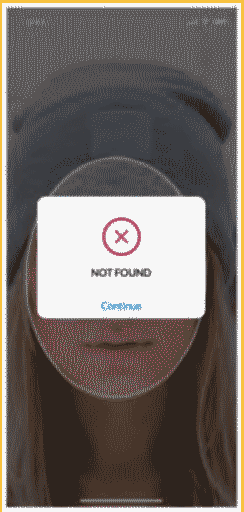

- Do steps 2-5 every morning at 2am as the 700 or so available slots for appointments vanish over a few minutes. Yes, including the registration– every morning, enter all of that information as fast as you can, take another photo, or as many as it takes, and keep trying,.

A 27-year-old Cuban woman, who also requested anonymity over concerns that recognition would affect her entry into the U.S., told Rest of World she’d been waiting on the Mexicali-Calexico border penniless with an infant for over a month. ‘I have to wake my 3-year-old baby at 2 a.m. every day to enter our information and try our chances with the app.’ She said she had used the auto clicker to tap over and over on the photo she had to upload to get an appointment. ‘What I have noticed is that auto-clicker apps work mostly when there is only one person trying to get the appointment.’

Once a ticket scalpers’ tool, auto clickers now help migrants enter the U.S. : Migrants in Mexico are using automation apps to secure appointments with U.S. border officials

User Guide 6: May 12, 2023 (Direct Submit, post Title 42)

- Title 42 was lifted on May 11, and the vulnerability requirement is gone from the app.

- Haitian Creole is added to the app– sort of.

The quality of the current Creole translations is spotty at best. Users can only select Creole after a full user registration process in English and Spanish, including two-factor authentication. Error messages, drop-down menus, and navigation tools continue to display only in English. . . ‘Any human who is familiar with any kind of written language would look at that and say, that looks wrong,’ said Wagner, who recommends CBP hire language professionals to review the Haitian Creole text on the app. ‘It shows that they truly don’t care whether anybody understands it.’

Seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border? You’d better speak English or Spanish

- Appointments are allocated on a lottery arrangement, but with preference given to those who requested an appointment yesterday.

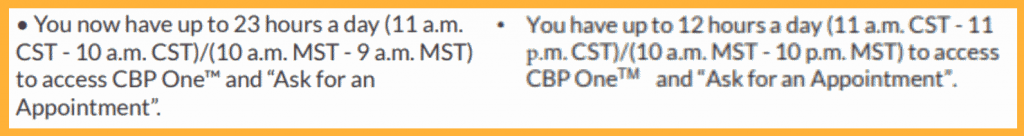

- You still must ask for an appointment each day, but you have 23 hours in which to ask for an appointment, and then another 23 to accept and confirm when you get a notification.

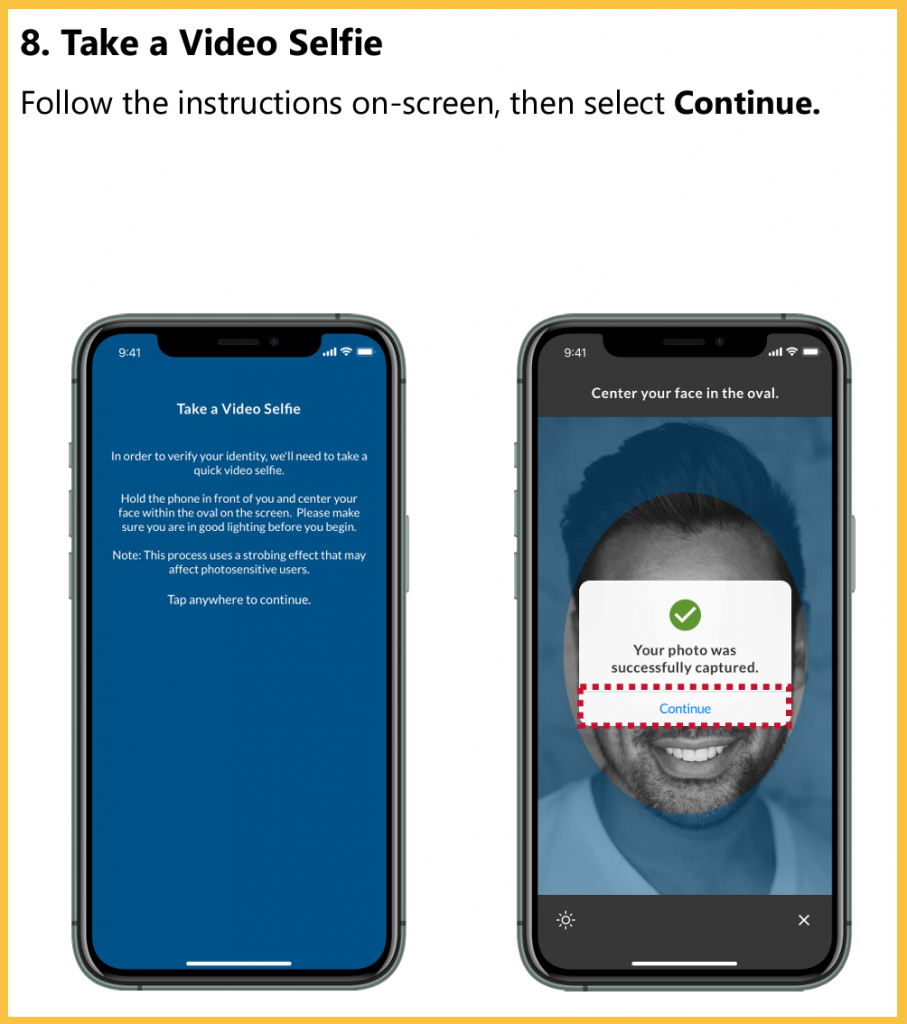

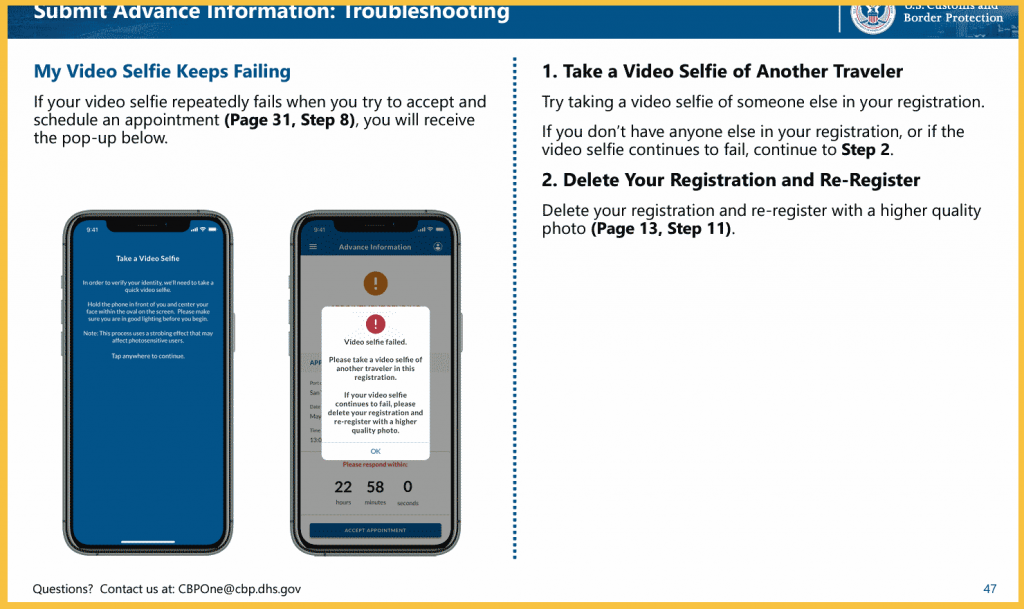

- Before you’re allowed to request an appointment, you must agree to share your location (and you must be in central or northern Mexico, including Mexico City and Guadalajara). Before you’re allowed to accept an appointment, you must share your location again, and take a “video selfie.”

Review the technology used (and not used)

Planned technology vs. technology utilized

One thing that stands out almost immediately:

Progress on the rollout of planned features for CBP One ground to a halt in 2021 as the app’s focus shifted away

CBP stopped adding capabilities to CBP One, and used them instead to make more apps

The new app was designed to have a “user centric interface to guide users with an intuitive and guided border entry/exit experience regardless of geographic location, mode of transportation or citizenship.” It would “eliminates the need for multiple CBP applications.”

When development of CBP One was announced, CBP had five mobile apps: CBP Jobs, ROAM, MPC (Mobile Passport Control), Border Wait Times, and CBP DTOPS.

As of this writing, CBP currently has eight apps: MPC, Global Entry, ROAM, CBP One, Border Wait Times, myCBP, ESTA, and CBP Truck QR.

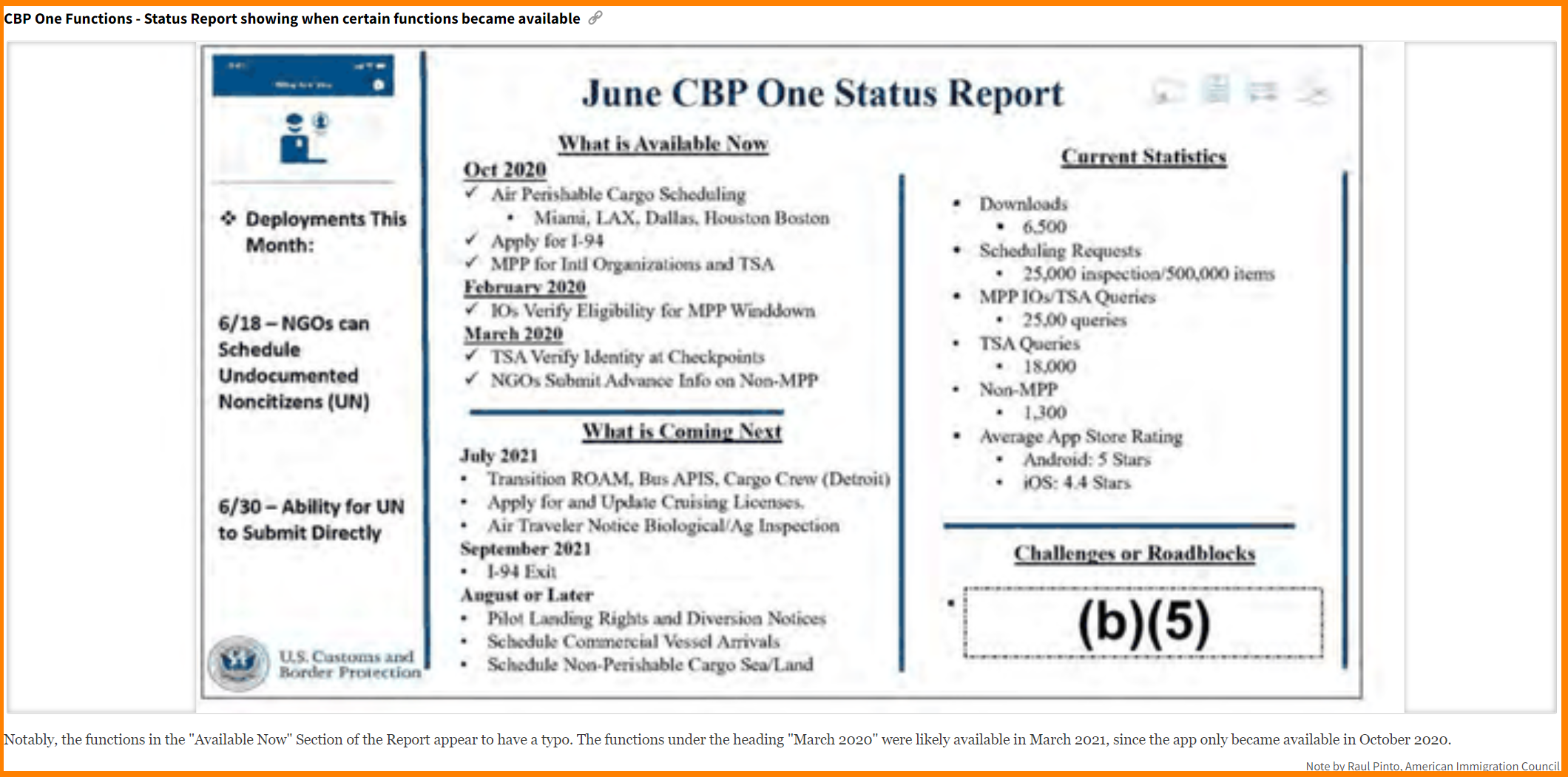

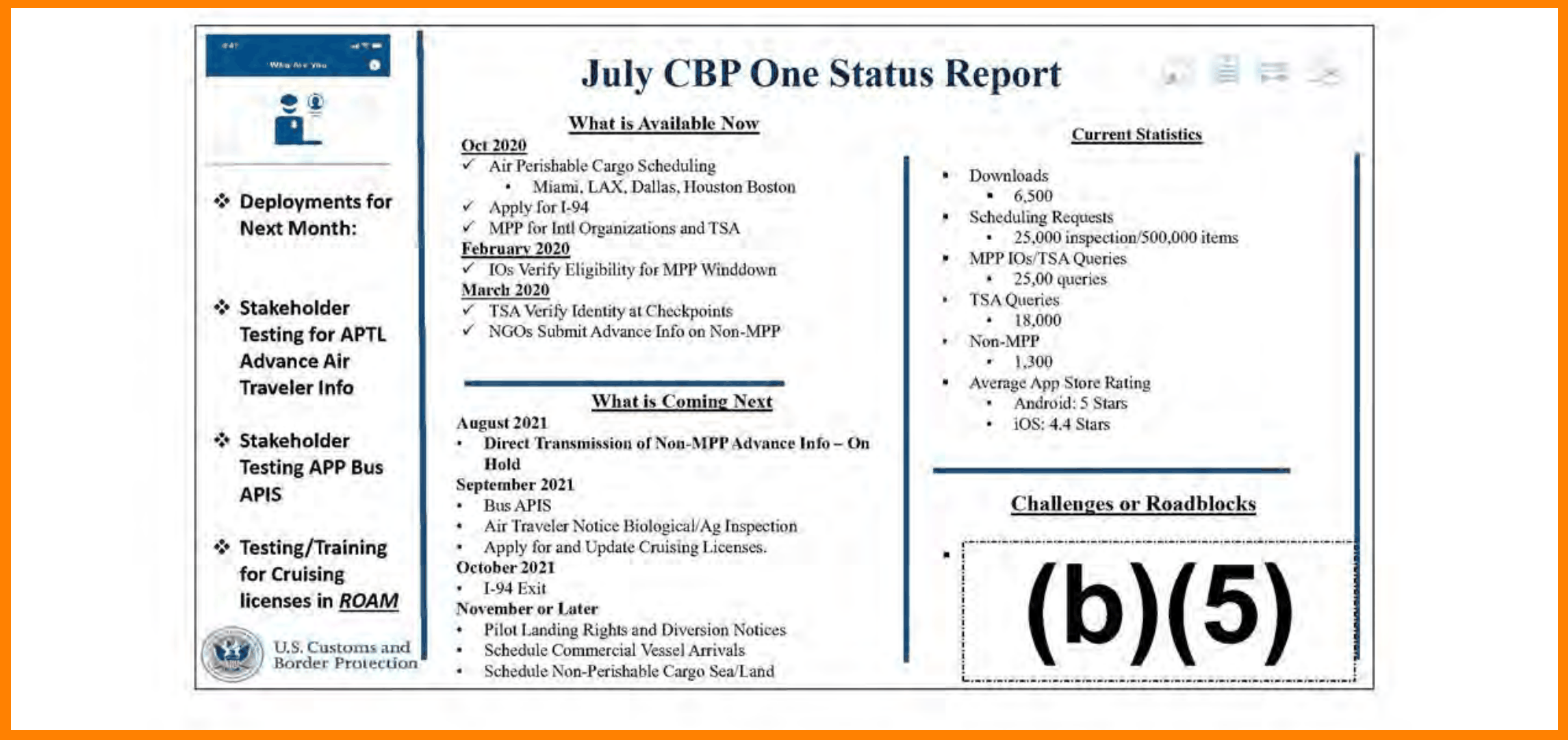

Development status reports showed a distinct lack of development

CBP published internal status reports for CBP One usage and available/upcoming features, which give an idea of how things weren’t progressing.

In comparing these status reports for June and July, a few things to notice:

- Under “What is Available Now,” features are listed as having been available in February and March of 2020, before the app actually launched in October. Presumably this was a typo and they should’ve said 2021, but the error wasn’t fixed from June to July.

- As of June 18, NGOs had the ability to schedule appointments using the app, but migrants using the app to submit their own requests directly was projected for the end of June, 2021. The July report says that the functionality had been placed on hold, and migrants didn’t get the ability to submit their own information until January of 2023.

- The “current statistics” are exactly the same for both months.

Facial Recognition Technology

Most of the criticisms about CBP One’s actual functionality concern its facial recognition technology. The background on that certainly explains some of the complaints.

CBP One was designed to comply with a biometric entry/exit mandate issued before apps (or the DHS) existed

Biometric identity information is used to identify or verify who you are based on physically distinguishing characteristics, such as your fingerprints, irises, or face. It suddenly became very important to the U.S. federal government in the wake of 9/11/2001, when for many, any shifty-eyed stranger on an airplane might be a terrorist ready to steer the flight into a building, and three months later, a fear of explosive shoes took hold of America and has largely kept its grip ever since Richard Reid completely failed to set fire to his.

The DHS cites multiple pieces of legislation from around that time, including the Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act of 2002’s Title III: Visa Issuance, as its mandate for gathering biometric data on travelers entering and exiting the country. The legislation references INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service), because DHS hadn’t yet been created as unification of USCIS, ICE, and CBP, all of which had previously been subsumed under INS, in 2003.

The relevant section reads:

Title III: Visa Issuance – Amends the Immigration and Nationality Act (Act) to direct the Secretary of State (Secretary), upon issuance of an alien visa, to provide INS with an electronic version of the alien’s visa file prior to the alien’s U.S. entry.

(Sec. 302) Sets forth technology standard and interoperability requirements (including October 26, 2004 implementation deadlines) respecting development and implementation of the integrated entry and exit data system and related tamper-resistant, machine-readable documents containing biometric identifiers. Requires a visa waiver country, in order to maintain program participation, to certify by October 26, 2004, that it has a program to issue to its nationals qualifying machine-readable passports that are tamper-proof and contain biometric identifiers. Authorizes appropriations.

The need to gather biometric information applying in all of these cases, it’s not surprising that CBP’s AI Facial Recognition Engine, Traveler Verification Service (TVS), isn’t just used in CBP One, but in TSA PreCheck, Global Entry kiosks and the Global Entry app, and the Mobile Passport Control App

CBP developed TVS to be scalable and seamlessly applicable to all modes of transport throughout the travel continuum. CBP has successfully implemented facial biometrics into the entry/arrivals processes at all international airports and into the exit processes at 32 airport locations. CBP also established facial biometrics at 26 seaports and all pedestrian lanes at both the Southwest Border and the Northern Border land POEs.

Statement for the Record on Assessing CBP’s Use of Facial Recognition Technology, July 2022

Facial recognition technology works in two very general ways:

- One-to-one comparisons for the purposes of verification, such as when you unlock your phone using your face to authenticate. This works by algorithms learning what your face looks like first, and then comparing future images of you to that original image, using it as a template.

- One-to-many comparisons for purposes of identification, such as when a photo is taken of someone in a crowd, and you identify them by comparing that photo to a database of photos of people that may include one or more photos of the person you’re identifying. These photos are also templatized, as in, they’re converted to a numerical pattern that is, ideally, specific enough to avoid making an incorrect match by false positives (matches to photos that don’t actually show the same person) or false negatives (overlooking images that show that person).

According to TVS’s first Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) in 2018, it was tested by employing CBP agents (in partnership with TSA) at airport departure gates, where they would take photos of travelers preparing to board the plane. Each photo would then be compared to a downloaded gallery containing templates from previously-acquired photos of the same traveler (such as a passport photo), and images of all travelers associated with the flight manifest, created using the Advance Passenger Information System (APIS) data

If a match couldn’t be found, a CBP officer would use a Biometric Exit Mobile wireless handheld device, or BE-Mobile, to manually capture the traveler’s fingerprint and use that to query a DHS-wide database called the Automated Biometric Identification System, or IDENT. Non-citizens’ facial images would then be retained in IDENT for use in future encounters with CBP.

The success of these programs led CBP to adopt TVS as its “accredited CBP information technology system that consists of a group of similar systems and subsystems that support the core functioning and transmission of data between CBP applications and partner interfaces.” It would use TVS as its “backend matching service for all biometric entry and exit operations that use facial recognition, regardless of air, land, or sea.”

Nevertheless, the PIA acknowledged, “While CBP may create APIS manifests on land border crossers via bus or rail, unlike travelers in the air and sea environments, there are no manifests created for pedestrian travelers to assemble a gallery of known travelers. CBP is developing processes that would enable the use of TVS at the land border; for example, CBP may briefly retain local galleries of travelers who have recently crossed at a given Port of Entry and are expected to cross again within a given period of time.”

A 2016 PIA for CBP’s Departure Verification System (DVS, TVS’s predecessor) described it this way:

At selected departure gates at select airports, CBP will deploy a facial recognition camera in close proximity to the airline boarding pass reader. This camera will match live images with existing photos from passenger travel documents assembled based on flight manifest data of the boarding flight. Upon receipt of the passenger flight manifest and throughout the passenger check-in process, CBP will compile photos from the Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT), the Department of State’s Consolidated Consular Database, and U.S. Citizen and Immigration Service’s Computer Linked Adjudication Information Management System (CLAIMS 3) to build a flight-specific gallery housed in the Automated Targeting System (ATS).

. . . The test was scoped to include only one route and run until September 30, 2016; the pilot was later extended through November 2016. For flights operating on this route, a CBP-manned camera and tablet computer were placed between the boarding pass reader and the aircraft. As travelers checked in for their flight, CBP obtained passenger manifest data and assembled existing traveler photographs into a downloadable file that was pushed to the tablet prior to boarding. These photographs had been accessed from various DHS and Department of State systems. As travelers passed through the boarding area, the camera took their photographs. The real-time photographs were compared to the downloaded pictures to determine if CBP systems could accurately match the two photographs.

(Yes, this is what it’s like to read every Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA)– they’re clearly not intended to be consumed by, for example, the passengers on these flights. But though they’re public, they’re mostly about explaining how new technologies don’t violate any existing privacy regulations. IMO they could just as easily be called CYAs as PIAs, but YMMV.)

That gives you an idea of the conditions under which the TVS was developed: a very controlled environment composed of a brightly lit airport departure gate, where CBP officers (“CBP-manned camera”) were taking photos of travelers and comparing those photos to the travelers’ own photos from their travel documents, i.e. passport photos etc., as well as to the flight manifest.

A September 2020 GAO Report shows that FRT for land crossings was low priority– at best– when CBP One launched

The Government Accountability Office published a report evaluating CBP’s use of facial recognition technology (TVS) to date.

As of May 2020, CBP, in partnership with airlines, had deployed FRT to 27 airports to biometrically confirm travelers’ identities as they depart the United States (air exit) and was in the early stages of assessing FRT at sea and land ports of entry.

FACIAL RECOGNITION: CBP and TSA are Taking Steps to Implement Programs, but CBP Should Address Privacy and System Performance Issues

The report described, and included photos of, the scenarios of several pilot tests, looking at the accuracy of FRT but also the implementation of privacy safeguards and warnings. It included recommendations for CBP to be more diligent about displaying signage informing passengers of the Biometric Entry-Exit program and their right to opt out if they chose, as well as auditing airlines employing FRT for privacy purposes.

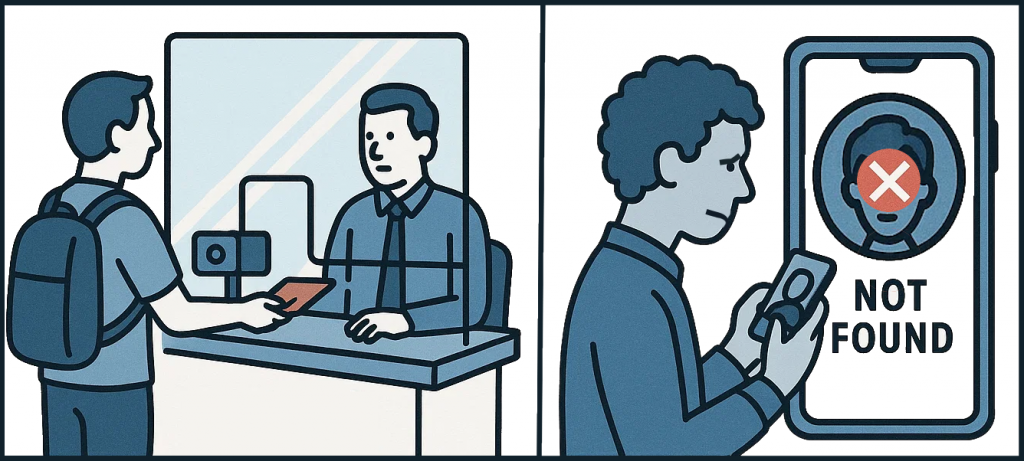

But the record scratched at the description of the process CBP had in place to test FRT for pedestrians:

As travelers approach the primary inspection booth and present their travel identification documents, such as passports or visas, cameras connected to TVS attempt to capture live photos. CBP officers scan the traveler’s identification document, which allows CBP’s TECS system to locate the document photo. Once the photo has been located, CBP’s system sends the photo to TVS. TVS then compares the live photo against the document photo to produce a match or no-match result. Travelers who are not matched by TVS instead have their identities verified manually (a visual inspection) by a CBP officer.

Here’s a rough approximation of what that looks like:

- You present your travel documents to the CBP Officer.

- A facial recognition camera takes a photo of you.

- That photo is then sent to TVS.

- This newly-captured photo of you is compared to the one in your travel documents.

- If a match isn’t found, CBP officers do a visual inspection to verify your identity.

Now compare that to the process in CBP One:

- You have no documents, so skip this step.

- Instead, you manually enter your information into an app, and that takes a photo of you.

- If the app accepts your photo, it will be compared to at least two databases that might or might not have your photo. You won’t know the results of that comparison.

- If you’re issued an appointment and want to accept, you’ll need to undergo liveness detection by taking a “video selfie.”

- If at any point something doesn’t work, too bad. No officers are around to give you a visual inspection, so this is where the process ends.

Sure, TVS might be doing the comparison– but nearly everything else is different.

The advantage in the first scenario couldn’t be more obvious– there’s an actual room, with CBP officers in it. In other words, you’re not using an app.

In a July 2021 report, NIST said that the quality of the camera and the environment in which the picture is taken affect the accuracy of facial recognition. Thus, the availability of CBP officers to check the accuracy of the systems conducting the photos’ comparison is vital to ensure racial minorities are not disproportionately impacted by the technology’s shortcomings.

CBP One: An Overview

And what about when something goes wrong?

In addition to random sampling, CBP officials can be informed of problems with air exit facial recognition if they are observed or reported by airlines or airports. For example, as previously mentioned, we observed a flight that experienced a high number of no-matches. When we alerted officials to the problem, they reviewed match data from other flights at that airport and identified similar issues. Specifically, CBP officials determined that lighting issues at a particular terminal were affecting the quality of the photos taken at the gate, and they worked with airport officials to address the issue. CBP officials also noted that they generate automated reports of matching rates and usage on a weekly basis, and provide weekly performance reports to stakeholders, such as airline partners. Officials said they use this reporting to gauge system performance.

So there was a problem, and officials were alerted to it, and they assessed the situation– probably in person– then determined that the lighting was affecting the quality of the photos. Also they generate automated reports weekly and report to stakeholders.

Does any of that come even close to applying to how CBP One is used? Note that this report came out a month before CBP One was launched, and the assessment of CBP’s facial recognition technology is that it’s very accurate when used in airports, except if there’s an issue with lighting or otherwise affecting the image quality– in which case CBP officials look into it and they addressed the issue. And they’re looking into applying FRT at land crossings for pedestrians, but that means pedestrians with passports and/or visas arriving on foot, in person, facing a camera operated by CBOs.

CBP might’ve been determined to use TVS as its “backend matching service for all biometric entry and exit operations that use facial recognition, regardless of air, land, or sea,” but if the vast majority of your pilot testing and general application of a technology is on air travelers, you are by definition excluding all undocumented migrants from your results. You are developing your technology to fit a scenario that does not include, and therefore cannot apply to, this audience.

This audience is composed of people using their own phones, on crappy wifi, by themselves with no help, most likely terrible lighting, and nobody noticing when it’s not going as planned. And when that happens, it doesn’t seem like it goes in anybody’s weekly performance report for stakeholders.

Statement for the Record on Assessing CBP’s Use of Facial Recognition Technology

In July of 2022, CBP submitted a statement for the record for a hearing titled “Assessing CBP’s Use of Facial Recognition Technology” before the House Committee on Homeland Security.

CBP is aware of concerns regarding biometric facial comparison matching, specifically that non-match results may be racially or demographically biased in performance. CBP does not track race as a descriptor during traveler processing; however, CBP data analysts have performed extensive operational analytics on TVS matching that shows a negligible effect in regard to biometric matching based on country of citizenship, age, or gender while achieving an average technical match rate of 99.4 percent on entry and 98.1 percent on exit. No changes have been necessary as the matching performance has remained consistent for several years across multiple matching algorithms. From January 2017 through the end of June 2022, technical match rates remained high among citizens from various regions of the globe, for example: Africa 99.5 percent match rate; Asia 99.3 percent match rate; Central America 99.6 percent match rate; and Europe 99.6 percent match rate. If a traveler cannot be matched by CBP’s biometric facial comparison technology, the traveler will simply be processed through the traditional inspection process consistent with existing requirements for entry into the United States.

Maybe you’ve already guessed, but this statement didn’t mention CBP One.

Liveness Detection

Wait, what’s a “video selfie”?

The first CBP One PIA has a brief description of liveness detection in the app, and it’s clearly not just talking about a photo.

CBP One™ prompts the user to take a live photograph or selfie (new photograph and not the same image collected from the passport/epassport). CBP One™ instructs the user to line their face up with a circle on the screen of their mobile device. CBP One’s embedded software then performs a ‘liveness’ test to determine that it is real person (and not a picture of a person).

First CBP One PIA

A footnote on that section reads:

While the user is taking the “selfie,” the technology embedded within the mobile application relies on the devices camera to view a live image through 3D face changes and observing perspective distortion to prove the image is 3D. If “liveness” cannot be confirmed, the user is unable to utilize the CBP One application.

This sounds very much like the iProov, product Flashmark, which “uses the screen of a mobile device to flash a unique, one-time sequence of colors, under server control, onto the user’s face. The server uses machine learning technology to analyze and determine if the image is a live person.” iProov received multiple CBP contracts to integrate “Genuine Presence Assurance” into CBP’s technology, starting in 2018.

This occurred to me when I read the monthly operational report from March 17, 2023, which states:

The large number of appointments scheduled via CBP One in recent months was made possible through the identification of process improvements and implementation of a number of software updates that fixed earlier reported technical difficulties. For example, CBP addressed reported challenges related to geolocation and error messages due to bandwidth issues with a third-party software for liveness.

First, I think that third party must be iProov.

Second, this is as classic an example of “bug fix that isn’t a bug fix” message as you could get — “The app worked really well, which was only possible because we fixed the thing we broke.” Or in this case, possibly “We made the third party fix the thing it broke.”

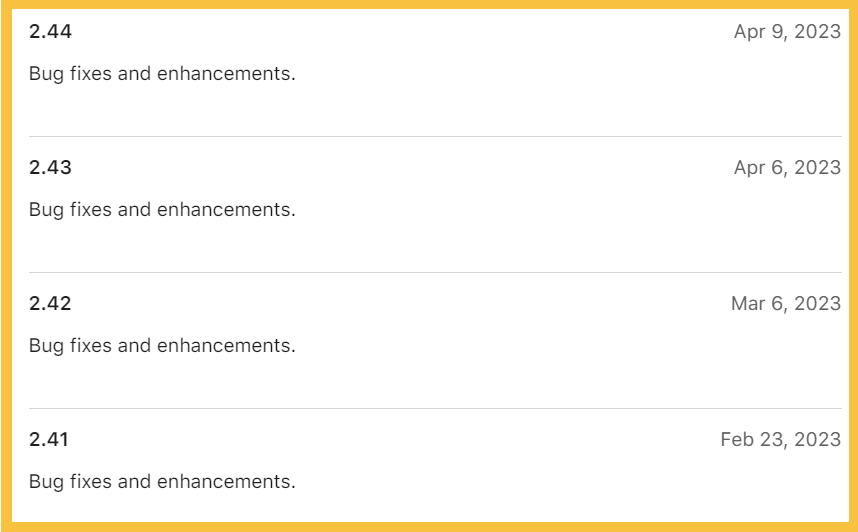

Third, bug fixes go in release notes. Or at least they should. But for CBP One, there are no release notes (see below), because the release notes go in monthly operational reports. Because of course.

A thread for someone else to pull on?

So many of the complaints about facial recognition point to studies, including by NIST, demonstrating racial and other biases in the technology, suggesting that this accounts for when Haitian refugees, for example, can’t seem to get the app to recognize them. In response both CBP and NIST point out that facial recognition algorithms improve rapidly over time, and that:

CBP has partnered with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to perform an independent analysis of CBP’s facial recognition performance, including potential impacts due to traveler demographics and image quality. Based on an algorithm vendor test conducted by NIST in 2019, it was concluded that the false positive differentials based on demographics were undetectable using the NEC-3 algorithm which is used by CBP. Per NIST, the NEC-3 is the most accurate algorithm evaluated (out of the 189 tested). CBP’s match rate is greater than 97 percent and improving.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Use of Biometrics (Knowledge Article)

(CBP partnered with Nec Corporation of America in June, 2017 – CBP’s OFO, United airlines, NEC Corporation tested facial recognition at Houston George Bush airport. Product: NeoFace® Express facial recognition stations)

However,

- That article doesn’t link to the actual NIST report on testing for demographic effects: Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT) Part 3: Demographic Effects

- False positive differentials are mentioned, but not false negatives

- The article specifically describes air travel and comparing photos to passports and visa photos (whereas the FRVT test also looks at border crossing images)

- It also doesn’t mention presentation attack detection (PAD), which is what the “video selfies” are for– to verify that that the camera is not just seeing you, but the actual you rather than, say, some imposter holding up a picture of you. It seems to me that this is an entirely separate area where bias might be introduced, which in this case would be in IProov’s territory rather than Nec’s.

But I can’t really give this the full examination it deserves. NIST has even separated out FRVT into two different areas, FRTE (Face Recognition Technology Evaluation) and FATE (Face Analysis Technology Evaluation), to make a clearer differentiation between FRT and PAD (to put it generally), and while it’s fascinating, it’s really out of my wheelhouse at the moment.

Still, I suspect that many of the complaints about bias are actually about liveness detection and not facial recognition.

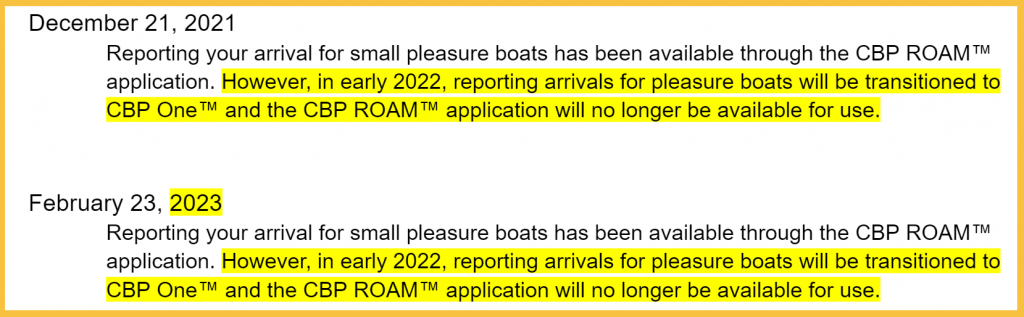

A note on ROAM (Reporting Offsite Arrival Mobile)

CBP’s app for pleasure boaters was on the app store in 2020 when CBP One launched. CBP One’s roadmap calls ROAM out as a service to be incorporated into the app within the first month.

And announcements about the app’s demise, which appear to have been greatly exaggerated, appeared publicly on the CBP One page since it was originally posted.

But not only is the app still around, CBP is still updating it– in September of 2021, they added a feature to apply for cruising licenses. Stranger still, ROAM’s description on the App store says “Disclaimer: This is a pilot version only for use in limited areas. Contact your local Port of Entry for guidance.”

The strangest thing of all might be this quote from the first CBP One PIA. That’s all of the information about it in the PIA, so I don’t know what happened with this functionality.

Reporting Offsite Arrival-Mobile (ROAM)

The ROAM mobile functionality is embedded into the CBP One™ mobile application and provides travelers arriving to the United States with an option to voluntarily self-report their arrival to CBP. In addition, the ROAM mobile functionality will automate existing manual data entry and law enforcement queries for CBP and provide a more sophisticated capability for conducting a remote inspection via video conference. This function will not be available at launch of CBP One™; CBP will publish a standalone, function-specific PIA to discuss the privacy risks and mitigations thoroughly. CBP will update this Appendix when the standalone PIA is published.

First PIA for CBP One

Walk through the documentation

Website

Here’s a screenshot of the first day of the CBP One website — February 23, 2021. You could guess the timing based on the blue box talking about MPP, but the rest of it with the orange arrows has been more or less standard since then.

It launched with a “Getting Started” section limited to a brief set of instructions to download the app, create a login.gov account to use it, then “users can access the different CBP services based on their specific needs.” It could have contained, for example, the Powerpoint presentations given to NGOs, or the January 5, 2023 fact sheet announcing that migrants could start using CBP One on January 12, but did not.

That’s as much time as I’ll spend on the website, which ordinarily would be the focus when talking about documentation for an app. But that’s exactly the problem, because there’s not much to say about documentation that’s incomplete and out of date, except that it’s incomplete and out of date. Which it is.

And I’m not actually sure how important guides are, here. They should exist, absolutely, and they should be up to date, absolutely. But the guides do not tell you what to do when the app crashes over and over again, erasing your registration and taking you back to the login screen. They don’t tell you what to do if you can’t create a login, register a traveler or request an appointment. But there is one troubleshooting item you will see. They won’t tell you what a video selfie is, or what it’s used for, but if it fails– take a video selfie of someone else. Or delete your registration and start over.

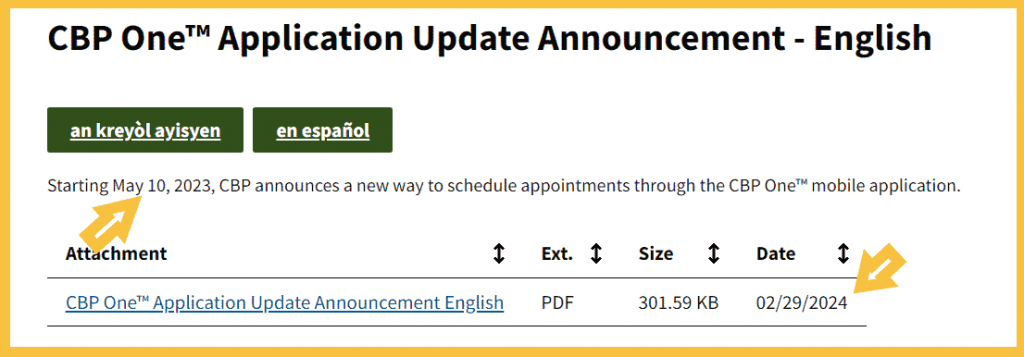

Update announcements

Since January of 2023 when the Biden administration announced that migrants would use CBP One to submit their own information, there have been two update announcements posted to the web site: May 5, 2023 (announcing an update for May 10) and February 29, 2024, which…might not have been announced at all, actually, since the page doesn’t seem to notice that it’s changed.

That might be because the time in which you can make an appointment has actually gotten shorter, for the first time since launch– as of May 10, 2023, you had 23 hours in which to request an appointment, and as of Feb. 29, 2024, you have 12. I can see why you wouldn’t draw attention to that unless you had to.

Release notes

What release notes?

Tech support

Well, umm…yep. That’s it.

Anybody try emailing this address? I did, and didn’t get any reply. Weird. Should I submit a FOIA request?

In-app documentation

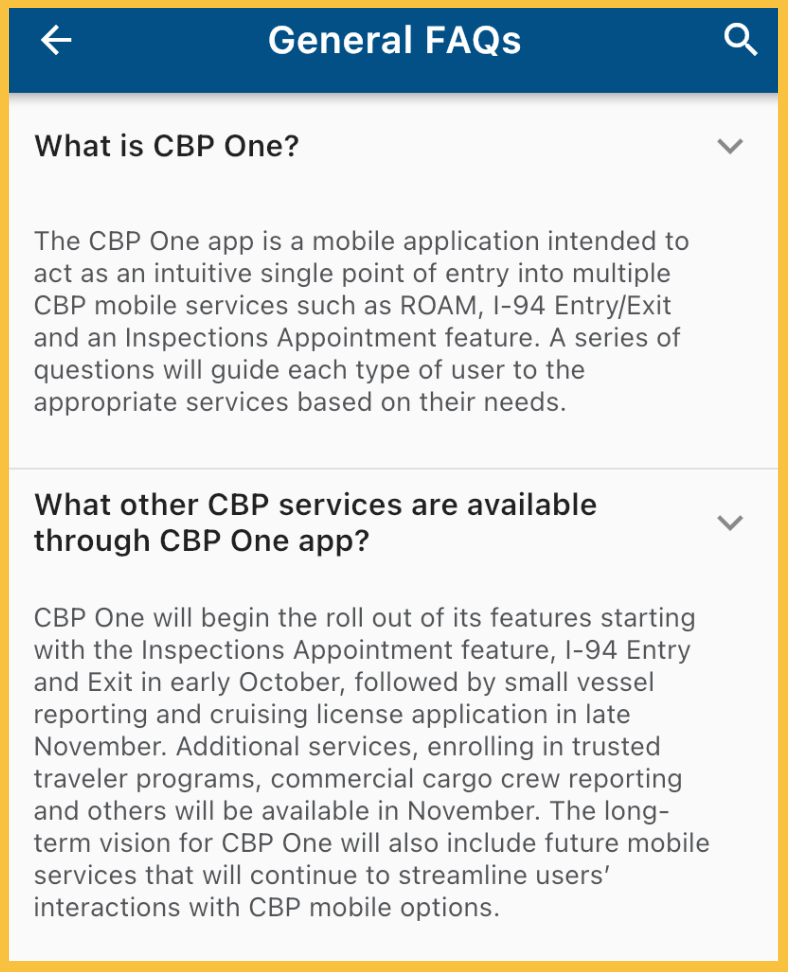

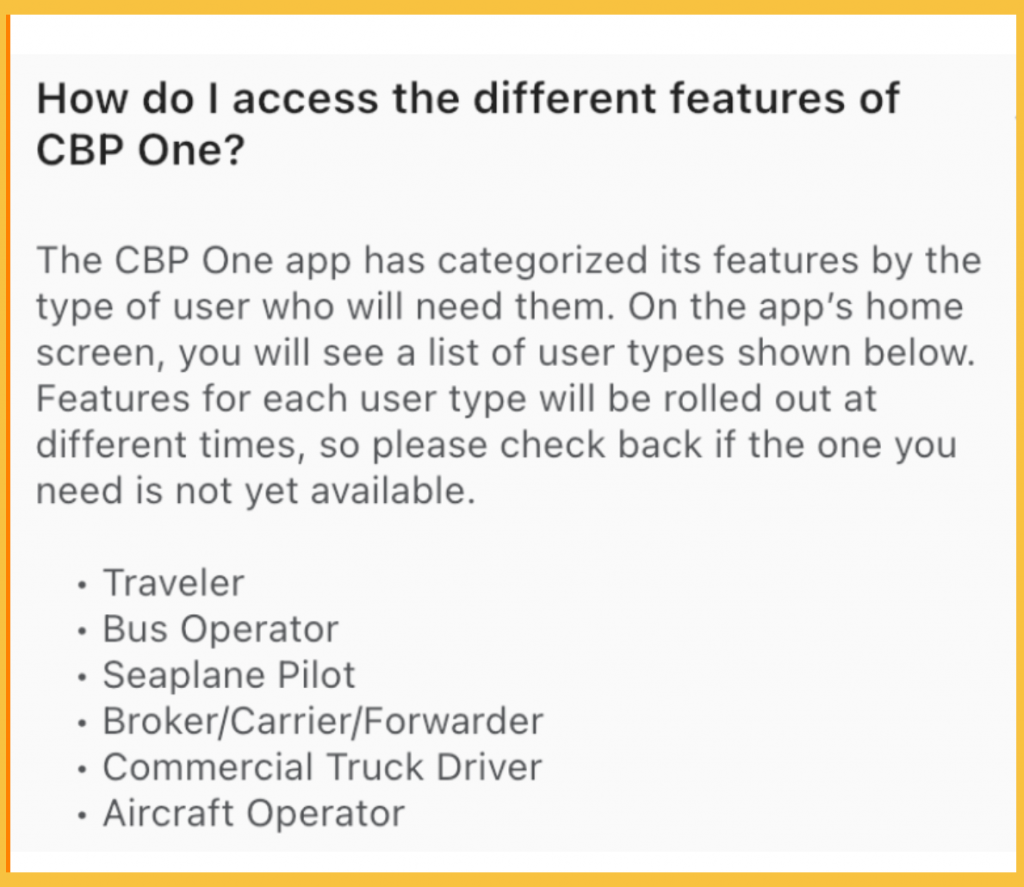

Recall that CBP announced the development of a new app, citing the need for a “an intuitive single portal for travelers and stakeholders to access CBP mobile applications and services such as CBP ROAM, I-94 Entry/Exit, and the Appointment Request Feature.”

The app officially launched on October 28, 2020.

The new app would be designed to have a “user centric interface to guide users with an intuitive and guided border entry/exit experience regardless of geographic location, mode of transportation or citizenship.”

It would, effectively, be a hub where users could be directed toward services based on their particular needs on the basis of their user type/role/persona (I’ve seen all three used interchangeably in documentation).

These screenshots describing CBP’s vision for CBP One are still visible in the app, on the General FAQs screen. As of this writing it’s mid-April, 2024, which makes you wonder which “early October” and “November” are referenced here. Based on what user types and features are actually available in the app, I have a feeling it’s 2020.

It’s like the app is haunted with ghosts of personas and services Never Yet To Come.

It’s like walking through a rental office space past a series of doors with signs on them, but if you open the door, all you see is a poster with cheerful text reading “Coming soon! Features for each user type will be rolled out at different times, so please check back if the one you need is not yet available!”

One of those rooms is, of course, full of hundreds of thousands of migrants, and that’s why the rest will remain empty. But you won’t see that mentioned on the signage.

What CBP One might have been

I give you the Mobile Passport Control app, developed by CBP with Airside in 2013:

Why the profound difference between the two?

- MPC is designed to help air travelers avoid some of the “agony” (as Hipmunk used the term) that other travelers experience when trying to comply with federal regulations.

- CBP One is designed as the only way for migrants to comply with regulations, thereby possibly relieving them of the “agony” experienced by migrants who aren’t allowed into the country at all.

In both cases, a select group is given an advantage over other groups in terms of complying with regulations set by the same entity extending that advantage. (Like TSA PreCheck, which allows travelers to pay to get through security quicker, and also uses facial recognition — and also seems like something everybody should get automatically, rather than an advantage you can pay for)

But I think it’s difficult to get our heads around the real, enormous, but hidden difference: every other program, every other app, is a choice. A real choice– the most you risk by not using them, maximum, is an hour in a security line.

CBP One, despite all statements to the contrary made by CBP itself, is not used voluntarily. Nobody would volunteer to use it. This is the kind of app you only use if you’re required, which sounds absurd as a design critique for an app. But it’s true, because CBP One is the most powerful app. The most you risk by not using it can be as costly as your future, even your life.

Evaluate criticisms of the app

The indignity of “glitchiness”

CBP One requires that applicants take a live photo. You can’t use an old selfie, and the app seems to have trouble with darker skin tones. And that is one of the glitchier aspects of this entire application, because the AI– the camera does not pick up certain phenotypes. And interestingly enough, when you get to that step, there is a model who is facing who’s on the screen. She’s a beautiful white model. And it’s surreal to watch an indigenous Mayan woman trying to take a photo facing this white model, and the camera just does not pick up her skin complexion. And that is often where the app crashes.

Gia Del Pino, Director of Communications at the Keynote Border Initiative, on Slate’s TBD podcast

Austin Kocher made an excellent point in a paper about CBP One last year:

I argue that while glitches productively call attention to the controversial processes of asylum digitization, representing technological barriers to asylum as “glitches” displaces political discussions about the right to asylum with depoliticized discussions about patching software problems.

Glitches in the Digitization of Asylum: How CBP One Turns Migrants’ Smartphones into Mobile Borders

Glitches are pretty generic, as it goes. They come in a few varieties that you see across all kinds of software, regardless of how frivolous or necessary it is. The glitches people have reported about CBP One for years now have pretty much remained constant in type – the FRT can’t recognize your face, or the geolocation thinks you’re already in the U.S., or the app crashes and takes you back to login repeatedly (something that happens to me quite a lot, actually).

It’s hard to say how frequently they’re occurring or where, or for whom, though, because CBP One’s documentation doesn’t tell us that. It doesn’t tell us what, if anything, it’s doing to fix them. This kind of dynamic is also pretty common– who works with software regularly and feels completely in the dark about when, or whether, a problem they’ve reported is going to be fixed?

What sets CBP One’s glitchiness apart is the very fact of glitches. To complain that your asylum app has glitches can at once be 100% legitimate, and 100% like complaining that your right to privacy burnt a hole in your hand. You should not need to protect against flammability in claiming your right to privacy. You should not have to protect against glitches to claim your right to asylum.

CBP could give away hundreds of thousands of iPhone 15s to hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers, coupled with power bricks that last forever. It could make CBP One the most user-friendly app on the planet. It could provide top-notch customer service. None of these things would, in the slightest, rectify the inherent indignity of predicating a migrant’s well-being on a program you download from the same place as Candy Crush Saga.

The United Nations doctrine against returning refugees to their countries of origin where they faced oppression sufficient to flee to another country is called the principle of “nonrefoulment.” It’s invoked in the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, a treaty that the U.S. entered into in 1967. It contains many provisions about treatment of refugees (spoiler: the U.S. doesn’t comply with most of them), but its central principle of non-refoulment is articulated in Article 33:

No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, member- ship of a particular social group or political opinion.

I like that term for a lot of reasons, such as how it firmly assigns the “foulness” to the location from which the refugee is fleeing, rather than on the refugee, as Trump recently did by calling migrants “vermin.” In that he echoed bigots across history who have made entire populations their targets of moral disgust, labeling them as parasites, pests, germs, etc.– that kind of rhetoric certainly aided in closing the border to even asylum seekers in the name of protection against Covid (extra ironic given Trump’s own stance on the disease).

Obviously the complaints about how CBP One works differ wildly between the two parties (Homeland Security Committee vs. the 26 signers to the 3/13/23 letter) but this means that at least theoretically, in some hypothetical scenario, both sides on this issue could work together to make CBP One a better app.

Now on the subject of migrant-hating Republicans, I must bring up the House Committee on Homeland Security. But since there’s no possible way to cover every outlandish claim they’re making about CBP One, I’ll look into one– especially since it involves a supposed “glitch.”

An “extensive investigation”

In September, the Washington Examiner reported that cartels are using virtual private networks (VPN) to skirt requirements that aliens signing up for appointments at ports of entry via CBP One be present in northern Mexico before making the appointment. Using these VPNs, the cartels can exploit vulnerabilities in the app and schedule appointments for individuals regardless of their location—all for a fee—and they advertise this “service” on social media.

NEW DOCUMENTS OBTAINED BY HOMELAND MAJORITY DETAIL SHOCKING ABUSE OF CBP ONE APP

A letter sent to Secretary Mayorkas on September 14, 2023 from Reps Mark Green and Clay Higgins claimed that cartels are using VPN connections to evade CBP’s geofencing requirement that applications be scheduled only from central and northern Mexico, based on an August article in the Washington Examiner. The article claimed that migrants from Guatemala were only allowed by Mexico to pass through the country to the United States if they had a CBP One appointment, which shouldn’t be possible to schedule from outside of Mexico, so that proved that the app had been “hacked” by cartels

In a follow-up article in the Washington Examiner in October of that year, CBP Spokeswoman Erin Waters was quoted as saying “Claims that the CBP One app has been hacked are categorically false. Criminal organizations and smugglers continue to prey on vulnerable migrants, lying to them and putting them in harm’s way. Here is the reality: The lawful and orderly pathways we have established have been bad for cartels and other criminal organizations seeking to exploit migrants.” She also pointed out that “Importantly, the CBP One app requires a user’s device location services and GPS data to verify their location before booking and confirming an appointment.”

The Washington Examiner (described by Media Bias/Fact Check as “based on editorial positions that almost exclusively favor the right and mixed for factual reporting due to several failed fact checks”) makes this claim about exploitation of CBP One’s geolocation by cartels selling VPN service based on “an extensive investigation that included a review of unclassified, internal DHS documents and communications,” but I see no reference to the details of this investigation in the article, and no way to view those unclassified DHS documents.

Yet the House Committee on Homeland Security Chairman not only used this article to make a claim of fact that “Mexican cartels are abusing the Biden administration’s expanded use of the CBP One app as part of their vast human smuggling operations,” but then itself claimed to have accessed those same “unclassified, internal DHS documents and communications.” So where are they?

The documents are still under review to determine the extent of DHS’ compliance with the Committee’s comprehensive request.

Umm. Admittedly, the extent of my research here is a) looking at other “news” posts on the House Committee on Homeland Security to see if they eventually released the documents from review (not so far as I could tell) b) reading those two Washington Examiner pieces closely, trying to find a link or something to the “unclassified, internal DHS documents and communications,” (no luck), and c) tweeting at Washington Examiner journalist Anna Giaritelli to ask if she’s seen them. But they can’t have just made up an investigation into internal DHS documents, right? I mean, they got a quote from CBP Spokeswoman Erin Waters saying they’re full of it. If they had evidence that they’re not, wouldn’t it….be somewhere?

…especially if the House Committee on Homeland Security is going to make that claim themselves, citing the Washington Examiner as their only evidence?

In the end, are CBP the only ones who like the CBP One app?

I’m not sure even they are big fans of it, but they do at least sound like they’re fans of getting information about migrants– both biographic and biometric– submitted via an app.

Biometric Partners | U.S. Customs and Border ProtectionFor partners, using biometric technologies advances their operations, so they can improve the guest experience and boost customer satisfaction. For CBP, using biometrics allows us to shift the focus of our Officers from administrative functions to core law enforcement duties, improving our ability to deter, detect, and prevent threats to our nation.

Fundamentally, what we’re looking to do is get rid of paper, get rid of manual processing steps, and let . . . us free up our time from border agents and others in the process so they’re spending less time staring at a screen, less time printing out documents, and more time actually on the front lines, doing their jobs keeping us safe. That’s been a core part of my role as CIO, and we’re going to continue to accelerate that with AI innovations.

DHS Chief AI Officer Eric Hysen goes on Politico Tech podcast

Typically, once an undocumented individual arrives at a land POE for processing, CBP Officers (CBPO) spend significant time collecting and verifying basic biographic data about the individual during the inspection process. One at a time, the CBPOs interview and collect information from such individuals during secondary inspection. The CBPOs manually enter the information into the Unified Secondary System (USEC). To streamline and increase processing capacity at land POEs, CBP uses the CBP One™ mobile and desktop applications to allow the advance submission of biographic and biometric information from undocumented individuals seeking admission into the United States.

CBP One PIA Feb. 19, 2021

Historically, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) received no advance biographic or biometric information prior to the arrival of undocumented individuals at ports of entry (POE). This lack of information increases the amount of time it takes CBP officers (CBPO) to process undocumented individuals upon their arrival. To streamline and increase processing capacity at land POEs, CBP is expanding the use of the CBP One™ mobile and desktop application to allow the advance submission of biographic and biometric information from undocumented individuals seeking admission into the United States.

Privacy Impact Assessment DHS/CBP/PIA-076 Advance Information from Certain Undocumented Individuals

But the March 13, 2023 letter to Mayorkas from Jesús G. “Chuy” García and 25 other representatives cited something I hadn’t noticed before:

According to DHS Guidance, asylum seekers or others seeking humanitarian protection cannot be required to submit advance information in order to be processed at a southwest Border land POE.

A footnote cited Guidance for Management and Processing of Undocumented Noncitizens at Southwest Border Land Ports of Entry, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (Nov. 1, 2021), which is a letter to William A. Ferrara, Executive Assistant Commissioner, Office of Field Operations, from Troy A. Miller, Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, expressing that exact thing:

Possible additional measures include the innovative use of existing tools such as the CBP One™ mobile application, which enables noncitizens seeking to cross through land POEs to securely submit certain biographic and biometric information prior to arrival and thus streamline their processing upon arrival. OFO also should accelerate ongoing efforts to digitize processing at POEs and more effectively use data to increase throughput. In developing these solutions, CBP should, as appropriate, collaborate with interested non-governmental organizations and other key partners, consistent with applicable privacy protections and civil rights and civil liberties.

Importantly, however, asylum seekers or others seeking humanitarian protection cannot be required to submit advance information in order to be processed at a Southwest Border land POE. The submission ( or lack thereof) of advance information should not influence the outcome of any inspection. CBP will continue to make admissibility and processing determinations on a case-by-case-basis at the POE.

According to this guidance, CBP One shouldn’t be the exclusive means for migrants seeking humanitarian protection to appear at the border legally for inspection– or even, possibly, the primary means for them to do so. It sounds like Miller was, in fact, suggesting that the CBP One app should be used like an app-– which is to say, a supplementary device that makes a process more convenient.

And according to the sources quoted above, it does indeed make the immigration process more convenient– for CBP officers. Obviously CBP isn’t a business, but if it were, then it would be the odd sort of business that makes an app for employees to interact customers, but primarily serves the employees rather than the presumed customer base.

In other words, CBP One is an app made for CBP, not migrants. It should not, according to Miller’s guidance, be used as a replacement for human-to-human interaction. But that’s precisely how it is used today.

Some closing thoughts

This is a story about the most powerful mobile app in the world, and why it shouldn’t be.

It’s strange and grandiose to put it that way, I know. But think of how under Title 42, this app is how migrants were able to claim exemption from being expelled from the border on the grounds of being potentially diseased.

They did so on the basis of meeting certain “vulnerability criteria”– literally, there was a list in the app, and migrants were required to attest that they personally, and/or their family members, fit one or more of those criteria (which, ironically, included physical illness).

Imagine having to tell an app that you fear for your and your family’s safety where you are, so that hopefully some human somewhere will see it and decide to help you. Then imagine not being able to.

There’s no list of vulnerability criteria in the app now, because Title 42 is no longer in effect. Which is good, because it means you won’t be summarily dismissed from the border on the grounds that you might be diseased. But also bad, because at this moment it’s functionally the only way to request asylum under the Biden administration’s Circumvention of Lawful Pathways rule.

No one has to look you in the face to tell you that your misery doesn’t count, that your suffering isn’t great enough, to even give you a chance at finding a safe place to just live your life. Work, pay taxes, have kids, send them to school– just like everyone else.

And this app won’t let you tell them how badly you need it. And this app won’t let you tell them you deserve it, just as much as anyone else. And this app won’t let you tell them it’s your right, even though it is.

This app won’t let you tell them anything, for that matter. It just lets you give them something– your personal details, your family history, even the shape of your face. What will they give in return?

Post-script

Let’s not forget that the literal Lady of Liberty was, and is, an eternal advocate for asylum seekers:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

The New Colossus

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

I searched for “The New Colossus” on the DHS site, and found a single link: to Emma, the virtual assistant on the USCIS website.

Emma is named for Emma Lazarus, who wrote the poem inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty about helping immigrants. Inspired by her namesake, our Emma can help you find the immigration information you need.

Look at the happy smiling people with questions for Emma that aren’t “How can I just enter the country safely with my family, find a job, make a home, and live the so-called American Dream?”

3rd Parties/Partners

- Nec Corporation of America. June, 2017 – CBP’s OFO, United airlines, NEC Corporation test facial recognition at Houston George Bush airport. Product: NeoFace® Express facial recognition stations

- SITA. 2017 – CBP, JetBlue, SITA pilot-testing at Boston’s Logan airport

- Airside. 2013- Developed Mobile Passport app with CBP.

- Vision-Box. 2017 – CBP, Delta, Vision Box pilot- testing at JFK. Product: Vision-Box’s vb i-match biometric eGates

- iProov. Received CBP contract to integrate “Genuine Presence Assurance” $750,000 in 2023, $190,000 “with three subsequent phases bringing the potential total to $800,000″ in 2018, $199,000 in 2020. Product: “Flashmark uses the screen of a mobile device to flash a unique, one-time sequence of colors, under server control, onto the user’s face. The server uses machine learning technology to analyze and determine if the image is a live person.”