One of my first-year classes in college was History of Theater, in which I learned how the Greeks built amphitheaters into hillsides, carving out a semicircle of seating for the audience around the stage to maximize. The scenery for a play completes the circle, just as it does for any show in an amphitheater today. It’s the structure providing the necessary atmosphere for the experience.

Imagine sitting in such a theater, watching Euripides’ Helen, and seeing the demigods Castor and Polydeuces (Helen’s pissed off brothers) descend into the scene by a wooden crane—a mechane — whereupon they put an end to all of this murderous nonsense, and everybody lives happily ever after. It’s a literal top-down solution.

That’s where the expression deus ex machina, or “god from the machine,” comes from. And it became used, and mocked, throughout the world of fiction as a plot device providing a too-convenient, cheap ending to a story.

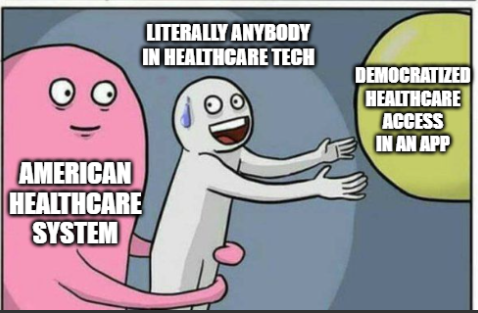

But my mind just keeps going back to that silly crane. It used to dangle a man dressed as a god before the audience, but these days he’d more likely be a techbro holding a smartphone, probably talking about the wonders of AI.

That’s on my mind today because in this post, I’m about to dangle a hypothetical mobile app in front of my audience– you. I illustrate our country’s mess of a healthcare system, and perhaps even reckon with it. This play isn’t ending any time soon, and we need to find a role in it (else one is chosen for us).

Healthcare data and analytics company Arcadia recently launched its own talk show, Spicy Takes, to discuss “hot perspectives in healthcare” while sampling—you guessed it—spicy food. The first episode placed President and CEO Michael Meucci in conversation with Chief Product and Technology Officer Nick Stepro and Chief Medical Officer Dr. Kate Behan.

I watched it while reading about their SDoH (social determinants of health) package, which promises to justify the time and expense required of providers to consistently record SDoH data by creating registries mapping that data with diagnostic codes, for use in proactively identifying patients at risk and connecting them to resources. While looking over the tear sheet, I heard Meucci say this:

I think that this is such a great platform for digital health as we start to think about how do you democratize access. Because if a patient is concerned that they’re not going to get the right treatment because of the color of their skin or the community they live in, the smartphone is a great equalizer. We talk about what’s changed for the last 10 years—that, to me is the biggest thing, the fact that you can pull out your phone and get connected with a doctor in 15 minutes.

“To your point, Stepro replied, “all of the technology and all of the access to healthcare in the world doesn’t change the fact that the single worst diagnosis you can have as a patient is being poor. You can’t address that with a healthcare institution. We can measure that poor people have lower outcomes but ultimately, we need to find and attack the problem of homelessness and poverty because you can’t just solve that in a clinic or with a smartphone.

I stopped reading and played that section of the show again. Meucci didn’t say that the healthcare industry can solve poverty with smartphones; he said we could democratize healthcare access. If that’s a spicy take then you can call me Spice Girl, because that’s my healthcare platform now. But I suppose coming from someone like him, that’s practically revolutionary.

And he’s right. As a country, America is primed for solutions like that: over 91% of Americans have smartphones. Even households without broadband hang on to their smartphones, because of course they would—it’s a tiny computer that can do more than any of us ever seem to realize, or ever will.

Democracy—another word with ancient Greek origins– literally means “power in the hands of the people.” What would it even look like to do that with a smartphone?

Let’s do a thought experiment to find out.

Time to design a smartphone app.

Imagine that in the beginning of The Legend of Navigating the American Healthcare System, our player character is given their first smartphone.

On that phone there’s an app installed (that I’ve just invented) called HACK: Health Agency, Care, and Knowledge.

Health – A full, patient-owned medical history

Agency – Control over your care, your records, your choices

Care – The power to find, compare, and advocate for treatment

Knowledge – Because to be informed is to be empowered

Does your vision of this app include it conferring access to all of an individual’s health records, stored securely but also accessible in their entirety at any time? If so, you’ve envisioned something better than what existing patient portal apps currently provide.

So yes, let’s absolutely start there, if we’re designing an app that democratizes healthcare in America.

And remember that democracy means that the power is in the hands of the people—not the “patients.”

Problem: we’re not in the driver’s seat.

Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) is the category of data on an EHR encompassing the non-medical factors affecting an individual’s health. In other words, your life, from the hospital where you were born (if you were born in a hospital) to the destination of your organs when you die.

They’ve been called the social determinants of health, but the word “determinant” suggests finality, immutability—that there’s nothing you (or anyone) can do about it. A driver, on the other hand, suggests that while the deck may be stacked against you, things could always change.

How easily could you could do that? *shrug* It depends, but we can safely say that “resident of the United States” is not an easy “driver” to change. We’re driving that road whether we want to or not.

And I hate to break it to you, but we live in a hostile health environment.

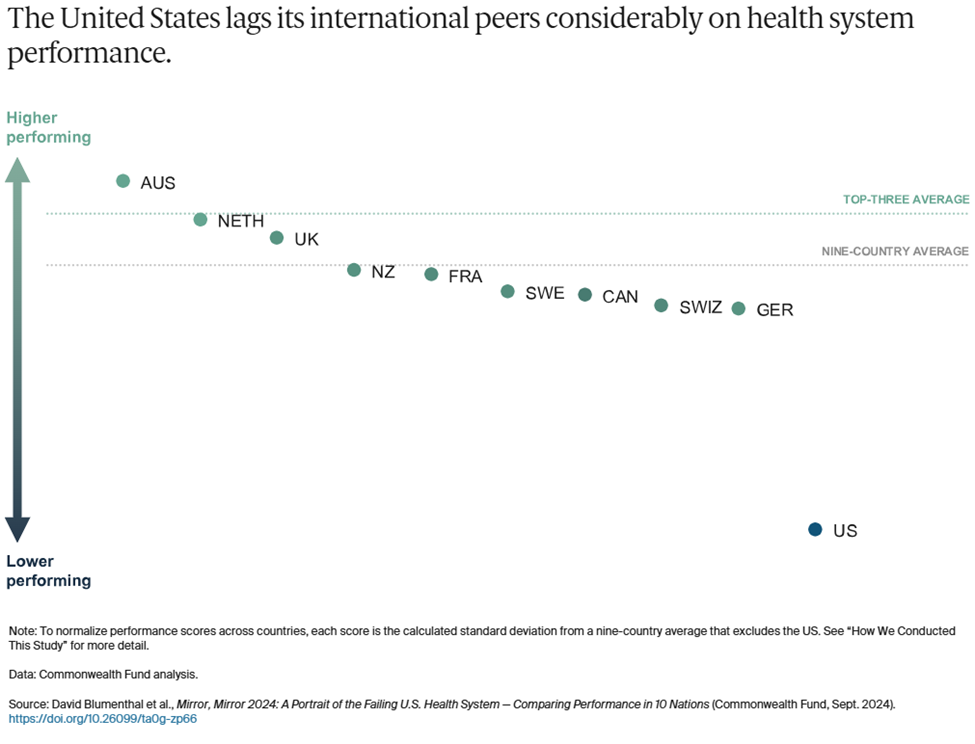

A 2024 study titled Mirror, Mirror 2024: A Portrait of the Failing U.S. Health System was conducted by The Commonwealth Fund to understand why America is doing so poorly by comparison—that is, going beyond the factor that rhymes with “schmooniversal schmealthcare.” The categories they used are:

- Access to Care

- Administrative Efficiency

- Equity

- Care Process

- Health Outcomes

In all but one of those categories, America comes in dead last or next to last.

To summarize the report, it found that Americans spend more on healthcare as a percentage of GDP to receive lower healthcare system performance than other countries. It faces the most barriers to accessing and affording healthcare. Its physicians and patients are most likely to face hurdles related to insurance rules, billing disputes, and reporting requirements. Equity in healthcare access and experience is low. And we live the shortest lives and have the most avoidable deaths. All by a longshot. USA! USA!

The one exception in these categories is Care Process, where we came in second. Their comments:

Care process looks at whether the care that is delivered includes features and attributes that most experts around the world consider to be essential to high-quality care. The elements of this domain are prevention, safety, coordination, patient engagement, and sensitivity to patient preferences.

I interpret this result as an indication that some version of enabling people to take charge of their own healthcare is key to accessing that care in spite of all other factors. It could even, possibly, raise America in those other categories where we’re currently ranking dead last!

Okay, probably not, but it could definitely help us face the hostile health environment in which we currently exist:

Misinformation is everywhere.

- We live in an era where vaccine misinformation spreads faster than the viruses they prevent, leading to the resurgence of eradicated diseases, overwhelmed hospitals, and preventable deaths fueled by fear rather than science.

- We live in an era where people google their symptoms and often reach the worst, scariest conclusions that inadvertently contribute to their paranoia, where “doing their research” on healthcare can lead to being convinced of conspiracy theories and pseudoscience.

- We live in an era where the president of the United States once advocated for injecting disinfectant as a means of staving off Covid, and in his next term has appointed a raw-milk-drinking anti-vaxxer as Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

- We live in an era where social media influencers with no medical expertise gain massive followings by promoting unproven “natural cures,” convincing people to reject evidence-based treatments in favor of detox teas, essential oils, and dangerous fad diets

We can’t afford anything.

- We live in an era where Cost-Related Nonadherence (CRN) is the primary reason for medical nonadherence (failure of patients to take their medication as prescribed due to cost) in some cases forced to choose between “treating and eating.”

- We live in an era where the term “dual ineligibility” refers to the status of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare, but are unable to access either one.

- We live in an era where medical debt is the leading cause of personal bankruptcy, where a single hospital visit can trap families in a cycle of financial ruin, and where crowdfunding platforms have become a substitute for a functioning healthcare system.

- We live in an era where rural hospitals are closing at alarming rates, leaving entire communities without nearby emergency care, prenatal services, or even a local doctor, forcing low-income patients to travel hours for basic medical attention they still might not be able to afford.

Neighbors hate and fear their neighbors.

- We live in an era where in transgender healthcare, patients frequently encounter providers who lack adequate knowledge of gender-affirming care or hold prejudiced views that hinder appropriate treatment.

- We live in an era where in reproductive healthcare, political and ideological barriers, including misinformation and ignorance, stand in the way of basic, safe medical care.

- We live in an area where Black patients are more likely to have their pain underestimated and undertreated, leading to worse health outcomes.

- We live in an era where in disability healthcare, patients struggle to have their pain, symptoms, and autonomy taken seriously, with providers sometimes dismissing concerns as psychological or unavoidable aspects of their condition rather than treatable medical issues.

- We live in an era where in chronic illness care, patients—especially women—are more likely to be dismissed as exaggerating their symptoms, leading to years-long delays in diagnosis for conditions such as endometriosis, fibromyalgia, and autoimmune diseases.

- We live in an era where in elder care, aging patients often have their autonomy disregarded, with medical decisions made on their behalf without full consent, reinforcing the notion that age diminishes a person’s right to control their own body and treatment.

- We live in an era where fat patients are often told to lose weight as the solution to every health issue, leading to delayed diagnoses and overlooked conditions that have nothing to do with body size.

- We live in an era where for immigrants, language barriers, lack of documentation, and fear of discrimination or legal consequences discourage people from seeking medical care, exacerbating preventable conditions.

But remember: “they” are us, and we all deserve better.

If you’re still thinking about this in terms of how we can help them by this point, stop it. That’s “patient engagement” speak, and our identify is not “patient.”

Our identity is “person,” i.e. member of the human species, class Mammalia, spending every second of life alive, for 100% of the time (until we’re not), thus making our health, and healthcare a relevant part of our lives 100% of the time. Yes, even for doctors.

We all should get a remote control.

A note on dignity:

Meucci mentioned not getting the “right” treatment based on the color of your skin or the community you come from, suggesting that a smartphone could be “a great equalizer.”

That’s a powerful thought, given the indignity that confronts many Americans when they try to interface with the healthcare system at any level, including when they see their providers—whether the providers intend that or not. The hypothetical HACK app, simply by virtue of being an app, confers a sense of dignity that we might not get in the doctor’s office, or indeed anywhere else.

As a survey on dignified care put it, “Dignity is at the heart of personalization. Dignity means treating people who need care as individuals and enabling them to maintain the maximum possible level of independence, choice and control over their own lives.”

We live in an era where America’s healthcare system does not prioritize dignity. Is it possible to claw some of that back?

If you’re going to design a healthcare app to democratize healthcare access for people, that includes you.

In another Spicy Takes exchange, Stepro observes, “Isn’t it better when the consumer is educated and activated—after all, it’s our own body on the line? I’m glad folks are turning to Google or GPT for answers, even if they aren’t perfect, because it shows a healthier dynamic.” Behan responds that unvalidated or wrong information is hard to overcome, and Stepro sarcastically asks if misinformation in medicine has been a persistent issue.

Well, yeah, those problems face all of us, don’t they? We all consult with Dr. Google occasionally, because it’s free, and you can consult it at any hour and ask it any stupid question you want. The downside is that the answers aren’t reliable and can’t substitute for what an actual doctor might advise. And Dr. Google has no idea what your full medical history is (not that you want it to).

Some third-party apps like Ada Health improve dramatically on Dr. Google by using symptom checkers based on verified medical information. Chatbots based on large language models can certainly look up your ailments and dispense advice, although you should be wary if they encourage you to eat rocks. If you’re fortunate enough to have access to the Wolters Kluwer’s UptoDate clinical decision support service, you can find loads of evidence-based data refuting social misinformation. You can even get mobile access to it, and at $60 a month that’s not too shabby.

It’s still pretty far from “free,” however, and UptoDate doesn’t know whether you have a medical condition that could make any recommendations it offers highly dangerous. But if that feature is integrated into the HACK app, you lose the danger of uninformed recommendations, and get to keep the endlessly useful medical library.

On that subject, what else can we pack into this thing?

What an app wants, what an app needs

So far, the HACK app has two big features:

A library of trustworthy medical information that you can consult for any reason, at any time, that’s informed by your medical history included in the app.

Your entire medical history, including all lab results, hospital stays, specialist care, etc. regardless of which healthcare provider you saw for any of these treatments.

Let’s continue stealing important features from other smartphone apps to integrate them into the HACK app, bearing in mind that they must be for the individual using the HACK app—not features designed for providers to gather data from, or to influence the behavior of, the patients they treat.

What else?

Let’s say the app has an UptoDate level of education materials in a database that connects to your specific data and diagnosis using MedlinePlus Connect. Give the app a chatbot that can pull from this database to answer all of your questions, regardless of how sensitive or embarrassing, and deliver that information in simplified terms without jargon. Now you’ve got a semi-omniscient doctor in your pocket who can tell your uncle (or RKF Jr.) to stuff it when he goes on about vaccines causing autism.

Let’s say the app prioritizes having control over your own data and lets you update and make corrections to your EHR data using a souped-up version of OpenNotes. It also includes a data permissions management dashboard, with the ability to see an audit trail of who has accessed that information—even if there’s nothing you can do about it.

Let’s say the app can also be a buddy who just happens to have a weird fixation on making sure you follow your treatment plan. It incorporates behavior modeling tools from Health Catalyst’s UpFront app to take over remembering stuff when your brain is full (i.e., cognitive offloading). “Hey, you were supposed to schedule that colonoscopy three weeks ago—want me to go ahead and set up the appointment, ya big baby?” Okay, to be fair, Upfront would be nicer than that.

Let’s say the app can create a localized map of all healthcare providers and resources in your area that you can filter by available services. It builds this using tools like Unite Us’s resource directory or ZocDoc’s appointment booking platform, but no referrals are required—you self-refer. “Hi, I have a weird rash and need to see somebody within a week. What do you have available and how much is it going to cost?”

Let’s say the app also has a filter that flags conditions you have, and procedures you might need in the future that might become, you know, illegal in your area at some point. The app could tell you the next closest location where it’s still legal, and point to ride-sharing and other assistance to help you get there/afford it. It could even alert you to events like Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton suing HHS to slide past HIPAA protects to access data indicating you had an abortion.

For that matter, the app could shield you from (some of) the effects of federal cuts to health services with built-in compliance to existing regulatory measures that protect and preserve your data.

Let’s say the app has access to population health data showing the health risks you face most imminently and what you can do about them, incorporating those insights from Arcadia’s population health platform and Health Catalyst’s Ignite platform. The risks matter whether they’re nature or nurture, and you need to know ASAP what you can do about those affecting you.

Let’s say that provider map also lets you sort by pricing, using resources like ClearHealthCosts. It could point out doctors working to alleviate medical debt in partnership with Undue Medical Debt.

Finally, let’s say the app, while placing all of this individualized information and these resources in a little device in your individual hand, also puts you in touch with communities of other human beings affected by the same conditions you are, by offering a feature like HealthUnlocked. You were never alone in this, and here’s the proof.

Nice little fantasy app you’ve got there. Who’s going to make it, though?

Ah, the mask has fallen. The jig is up. The cat’s out of the bag, and the deus is off the machina. What now?

Just kidding. This is a thought experiment for a reason—I don’t expect anyone to make the app. America is ripe for such an app, we need such an app, and we have the tools to create such an app—but that doesn’t mean we’re going to.

But let’s continue to be optimistic– perhaps I’m wrong on that second point. So, okay, what would developing the HACK app require?

- A governing body to make sure the app is trustworthy

- A sustainable funding model (Stop laughing– we just got started!)

- Interoperability across all EHR vendors (I said stop laughing!)

Assume that we have satisfied all three requirements. This is, once again, a thought experiment.

Now, can we seriously address the matter of who makes the HACK app– and why?

What are our options?

The ONC

This one is obvious, because they already oversee FHIR and TEFCA, and interoperability is their dream. They also have regulatory power without a profit motive. But they don’t make software—they just regulate it. Somebody else would have to make it, and put the ONC in charge.

A private tech company (e.g. Microsoft, Google, Apple)

Microsoft attempted something similar with HealthVault, a site where users could store and share their health information, which fizzled and died in 2019.

Google Health was born in 2008, died, and then came back again, finally dying off for good in 2023.

But Apple Health is alive and kicking, using Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) to let users import and view their health data on their iPhones and iPads after retrieving it. FHIR standards, importantly, were developed and adopted after Microsoft and Google made their respective shots.

When Microsoft and Google started leveraging FHIR, they were no longer in the “patient records for patients” business. Azure Health Data Services and Google Cloud Healthcare API are data platforms used by healthcare systems, payors, research institutions, and so on.

But in none of those cases was the focus on providing services based on patient records—just the records themselves. Apple Health can only function as a sort of meta-patient portal, requiring users to log into their actual patient portals to access their records, and their providers have to agree to letting Apple share the records in the first place.

If a private company like this developed the HACK app, you could argue that it democratizes access far more than the patient-portal-like products these companies previously developed, but, again—it would be their product, for better or worse, and arguably so would we.

A public-private partnership

This means:

- Private tech company builds the infrastructure.

- Nonprofit coalition manages the project.

- ONC (or other federal agency) sets the standards and governs the data.

I guess that’s an option. But if this combination of entities could accomplish something like the HACK app today, why haven’t they done so already?

Who’s going to own it?

Taking on the project of creating the HACK app through that kind of partnership would be a tacit admission that the current system has failed, and that it’s going to take an app to save it—or at least, to survive in the face of that failure.

That’s the paradox of designing a “subversive” app promising to democratize healthcare through the backdoor, while only requiring access to all of the health records that healthcare systems are refusing to share right now, even after the ONC has hounded them to do so for over 20 years.

Each of the app’s features “stolen” from an existing technology really would have to be stolen, and it’s hard to imagine healthcare tech companies welcoming someone pirating their platforms.

On the other hand, it’s also hard to imagine a better example of the healthcare industry doing what it can to make a difference. “I helped someone understand their own medical records and make plans for future treatment today, when otherwise they wouldn’t have” is not nearly as sexy a claim as “I helped someone out of poverty today,” but it’s a lot more realistic– and on a higher scale, both of those claims could easily be true.

But because healthcare tech platforms sell patient engagement tools to providers rather than to people, there’s no motivation to develop a HACK app per se.

And even if the motivation was there, America has a population of—what—over 340 million at this point? How’s the HACK app going to reach all of us, even a large fraction of us?

How do we get this kind of reach?

Let’s assume that the HHS is developing the app—it would have to, to approach anywhere near that reach.

I’ve actually done a lot of research and writing lately about another app, developed by another U.S. federal governmental department, that reached as many as 64 million—while also stringently adhering to high security and data protection standards and relying on nationwide interoperability and data integration. It’s installed on my phone now, actually, though I’ll admit that I haven’t used it recently.

Maybe the HACK app could take some lessons from it?

- Federal development and oversight—If HHS takes direct ownership of the app, just as this other agency did, that would mean developing the app in-house rather than outsourcing it to private industry.

- Security and data protection—The HACK app would need to encrypt personal data, require strict user authorization as well as access control and permissions management, and comply with federal security standards, just as the other app did.

- AI and automation for user navigation—Both apps rely on automated data processing, proactive notifications and engagement, AI-driven risk assessment, and smart eligibility and routing systems that guide users through decision trees based on their data.

- Large-scale user support and infrastructure—Both apps must be scalable to handle millions of simultaneous users, both use mobile-first design, and both require redundancy and real-time threat monitoring for resilience against system failures and cyberattacks.

That’s a very general list of requirements, but if another government-developed app can succeed on this level, couldn’t the HACK app do the same? Assuming that the HHS has access to all information and other resources required to do it, that is.

Now, if your answer is “Yes,” how shocked will you be to learn that the other app is CBP One? You know, the app developed by Customs and Border Patrol to scan the faces of migrants and use that as a basis to determine if they can enter the country? The one that Trump shut down on his first day in office, forcing me to defend it after bashing it for months? Yes, that one.

I know, different government agency altogether. Different goals, altogether.

But that’s my point– regardless of how you think about immigration or healthcare, it says a lot that even after such an app was (successfully) developed to regulate immigration, it’s impossible to imagine the government developing a similar app to get healthcare access to Americans.

CBP One has something else in common with regular patient portal apps—it wasn’t developed for its intended end users, but rather the organizations providing the app. And as with patient portal apps, that didn’t stop government officials from boasting about how the app provides migrant empowerment—”There’s a lot of people who would love to migrate to the United States. In essence, they see CBP One as sort of a self-petitioning mechanism that we’ve never had before.”

*cough* So, anyway…

After all of this, have we democratized access to healthcare yet?

No, but we’ve shown that it’s possible to make a tool for getting there.

The U.S. in 2025 is a country:

- where the best way to reach the greatest number of the population, regardless of demographics, is via a smartphone

- with a disaster of a healthcare system that we have no choice but to navigate

- where, within in that system, our healthcare needs are socially driven out of our hands

- where huge advancements in healthcare technology have been made, and continue to be made, every day

- whose government has already built a large-scale, high-security, interoperable app for mass data processing, supporting daily access by millions of people. Granted, that was for a very different purpose– but still, they did it

All of the problems standing in the way have been solved—just in different directions, for different people, with different purposes.

And now, the goddess Panacea would like a word.

She’s been quietly waiting in the wings, refusing to step anywhere near that cursed crane, even though she’s arguably the most qualified to do so.

She wants us to remember that America is now an older country than it ever has been, and older folks are sicker folks. They’re also notoriously bad with tech—but they’ve come far since the days when everybody was posting screenshots of their parents failing spectacularly at texting. And we’re at the point where the first generation to grow up using computers is eligible for AARP, anyway. So while the HACK app won’t replace their knees later on, it would be the next best thing to having a personal nurse (or tireless family member) with them 24/7.

She also points out that administrative efficiency is one of the categories included in the Commonwealth study where the U.S. tanked, with wasteful administrative spending estimated as high as $570 billion in 2019. And the HACK app could streamline patient access to records, real-time cost transparency, and insurance verification outside of the doctor’s office. Just sayin’.

Lastly, she wants us to know that the deux ex machina isn’t always what we think it is.

If your job is making boots, and you make boots for soldiers to wear to go to war, then boots are not your deus ex machina for winning the war. They’re just the tiny but significant contribution you can make, using the power and skills you have, to make winning the war more possible.

Likewise, if you’re in the business of making healthcare apps, your apps are not your deus ex machina for democratizing access to healthcare—they’re the tiny but significant contribution you can make, using the power and skills you have, to make democratized access to healthcare more possible.

She departs stage left with a warning: Stop hanging gods from cranes, she says. Just build some damn ladders, and let people climb.